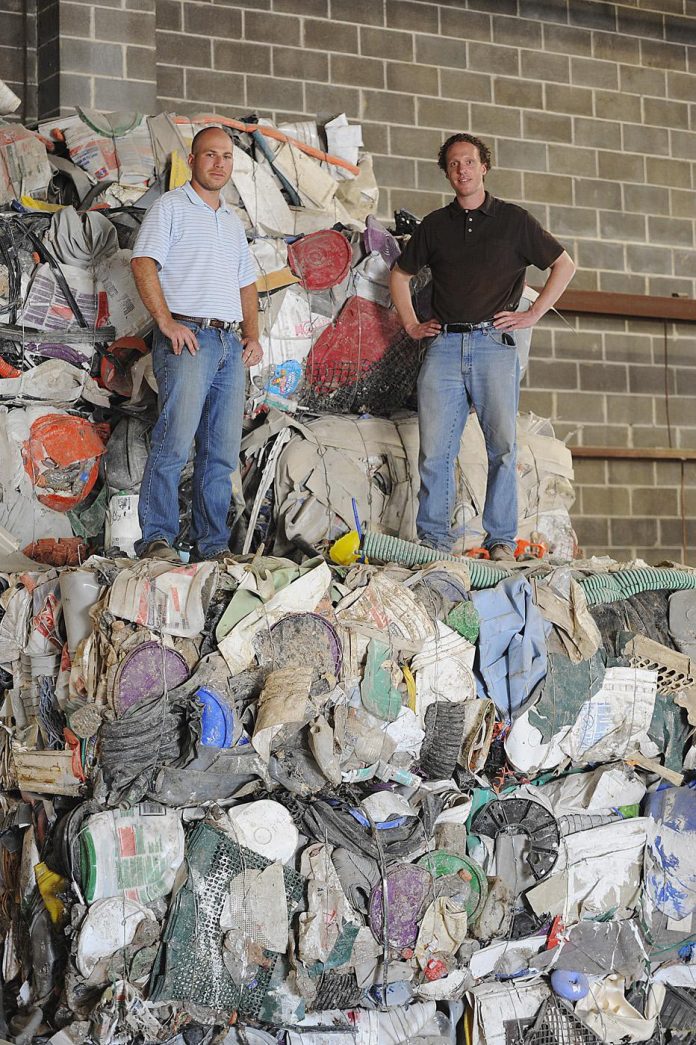

Avi Golen (left) and Jon Wybar own Revolution Recovery, a construction material recycling plant. Below, workers sort recyclable debris. JENNY SWIGODA / TIMES PHOTO

In a time of recession, or perhaps depression, Avi Golen and Jon Wybar are hiring.

And in a time of consumer waste and overflowing landfills — along with possible global warming — Golen and Wybar are recycling.

These are just a couple of the anomalies that the two self-described construction industry outsiders have created in Northeast Philadelphia’s Tacony section with their growing company, Revolution Recovery.

Seven years ago, Golen and Wybar — who met in the mid-1990s as students at the William Penn Charter School — partnered with the idea of recycling old and leftover building materials from demolition and construction sites. Two years later, they moved their mom-and-pop-sized operation into a 4,000-square-foot yard in Southwest Philadelphia.

Thanks to steady growth, they moved in 2008 into a recently vacated industrial site at 7333 Milnor St.

Today, Revolution Recovery collects about 200 tons of unwanted mixed building materials daily. The waste includes drywall, wood, masonry, cardboard, metals and other materials.

MAKING GOOD USE OF WASTE

Under normal circumstances, the tonnage likely would end up in a landfill. But Golen and Wybar divert about 80 percent of it for reuse and, in the process, have created their own sustainable and potentially profitable business venture.

For now, most of the profits are being reinvested in the company. The founders declined to discuss specific financial figures for this article.

“We had no know-how, no customers and no experience, which really was a blessing,” Wybar said, recalling the earliest days of the company.

“Had we had any experience or know-how, we would’ve said, ‘No, we can’t do it.’ But we took a fresh look being so naïve.”

“Our whole business is diverting waste from the landfills, whether it comes from a big company, a private homeowner or a small contractor,” Golen said.

Though the inspiration for the concept came much earlier, the nexus of their partnership formed perhaps not coincidentally one day in 2004 during a mountain bike ride through Wissahickon Valley Park in the city’s Northwest section.

Golen had graduated from the University of Colorado at Boulder with a marketing and advertising degree and was working as a truck driver, hauling waste from building sites during the height of the home-construction boom.

He saw contractors paying exorbitant amounts of cash, generally without a second thought, to dispose of countless tons of unused building materials along with equally wasteful wood-frame and cardboard packaging.

Contractors would buy material, such as drywall and lumber, in bulk. Any remnants went into the trash trailers.

THE CLEANUP COMMODITY

“There was a lot of good material left,” Golen said. “I saw all of this clean wood, clean cardboard and clean drywall. I knew it was a commodity.”

At the time, different recycling companies would take different materials and pay for them. But contractors couldn’t be bothered to sort and deliver it all to various locations.

Meanwhile, Wybar was wrapping up a stint with an environmental company working on the World Trade Center cleanup. He had graduated with a geology degree from the University of Texas at Austin. He was doing indoor air testing.

Golen pitched the partnership during the bike ride. Wybar parted ways with his employer and joined his old high school pal.

It was a two-man outfit from the start. They collected, hand-sorted, transported and sold everything personally. One of the biggest challenges was convincing contractors to buy into their concept.

Construction folks usually drive a hard bargain and are largely resistant to change. The environmental angle doesn’t often work without a financial one.

“We found that we very much have to compete on traditional prices and services,” Golen said.

Fortunately, the partners found plenty of wiggle room in the rates that contractors already were paying for waste removal. Besides that, Golen already had a big account lined up.

Swarthmore College was building new dorms at the time. In what they described as a pilot project, Golen and Wybar agreed to take leftover drywall from construction and process it for reuse in an on-campus arboretum. Drywall contains the mineral gypsum, which also can be used as a fertilizer and soil conditioner.

TAKING THE LEED

Based on their work at Swarthmore, the partners earned Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection certification for their process, which gave them additional leverage with other contractors, particularly those seeking LEED certification for their own construction projects.

Created by the U.S. Green Building Council, LEED certification recognizes Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design. Federal, state and local governments offer financial incentives for LEED-certified construction projects.

Developers can get credit for diverting a portion of their construction waste into recycling.

Since the Swarthmore job, Golen and Wybar have sold more processed drywall to a Salem County, N.J., company that uses it to make flooring products.

Revolution Recovery has innovated in other ways. Initially, client contractors can save money by sorting waste by type on the job site. But if that’s not feasible, Golen and Wybar offer single-streaming, where their company does the sorting in their 3.5-acre Milnor Street yard.

Much of the sorting is automated via conveyor belts, magnets and other machinery, but some of it must still be done by hand. The company has about 37 employees, including those in the yard and in executive offices.

Several factors make the founders think that demand for their services will only rise.

With residential construction booming in India and China, Golen figures that the prices of raw construction materials worldwide are bound to escalate. The market has already seen the value of copper tubing skyrocket, he notes.

Further, domestic construction will rebound eventually, resulting in a lot more construction waste available for disposal and recycling.

And even if one area of the recycling market tanks — for instance, if the price of copper plummets — the partners feel that they have enough diversity to withstand fluctuations. They’re already working to expand into the fiberglass, Styrofoam and carpeting markets, among others.

One potential threat to their model would be competition from major waste companies like Waste Management. What Revolution Recovery is doing is no secret to conglomerates.

“The big waste companies know what’s going on, and they’ll figure it out,” Wybar said. “But big ships are hard to turn. We got out ahead, and we want to stay ahead. We’ve been innovative. While they’re figuring out (how to handle) wood and drywall, we’re moving into fiberglass.” ••

Visit www.revolutionrecovery.com for more information about Revolution Recovery.