A cardinal is due in court. Maybe.

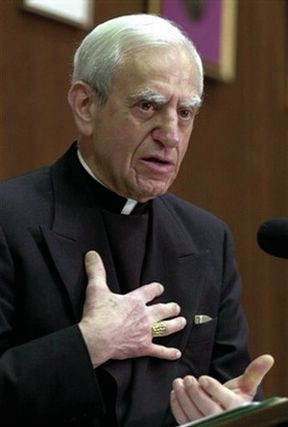

In August, a judge set Monday, Sept. 12, for a hearing to determine if ailing Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua is a competent witness in the sex-abuse trial of some clergymen and a parish school lay teacher.

But on Aug. 30, his attorney argued that Bevilacqua shouldn’t be required to come to court. So, as the Northeast Times went to press this week, the cardinal’s appearance before Common Pleas Court Judge M. Teresa Sarmina was not a certainty.

Earlier last month, lawyers for the city’s retired Roman Catholic archbishop and one of the defendants maintained Bevilacqua is ill with cancer and not lucid enough to testify at a trial. The assistant district attorneys prosecuting the case against three priests, an ex-priest and a former St. Jerome’s lay teacher maintain they need the cardinal’s testimony.

A decision on the cardinal’s competency as a witness could very well affect several civil cases in which Bevilacqua himself is a defendant.

Bevilacqua, 88, headed Philadelphia’s archdiocese from 1988 to 2003 when two minor boys allegedly were molested by some of the defendants and when one of the defendants worked directly under the cardinal’s supervision.

CHARGES ARE A FIRST

In February, Monsignor William Lynn, who was Bevilacqua’s secretary for clergy, became the first Roman Catholic administrator in America to be charged with two counts of endangering the welfare of children in connection with sex abuse cases even though it was not alleged that he had had any contact with minors.

Lynn’s lawyers argue that their client couldn’t endanger children because he had no duties that put him in contact with children. Prosecutors maintain Lynn had endangered children by allowing his co-defendants, James Brennan and Edward Avery, to continue to live in city parishes where they could have access to children even though he had investigated allegations of their sexual misconduct with minors.

Lynn, Brennan, Avery, the Rev. Charles Engelhardt and Bernard Shero all were arrested after a Philadelphia grand jury in February released its report on sexual abuse of minors by the city’s Roman Catholic clergy.

Lynn faces two counts of endangering the welfare of children and conspiracy. The others were charged with rape and related offenses and conspiracy. All have pleaded not guilty. A judge later threw out conspiracy charges against Shero.

Lynn’s attorneys, Jeffrey Lindy and Thomas Bergstrom, don’t want to see Bevilacqua on the witness stand. Last month, they told Sarmina that prosecutors had said they had not needed to question Bevilacqua while a recent grand jury was investigating sexual abuse of minors by clergy.

On Aug. 31, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that attorney Brian J. McMonagle on Aug. 30 told Sarmina that his client is too ill to appear in court and should be allowed to testify from his home.

A spokeswoman for a group of clerical-abuse survivors sneered.

“Bevilacqua wants the judge, the prosecutor and the public to do exactly what millions have done for years: trust him because he says so,” Barbara Dorris of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, said in an Aug. 31 e-mail to the Northeast Times.

During a scheduling conference before Sarmina on Aug. 5, prosecutors said they needed Bevilacqua’s testimony and wanted it videotaped, or “preserved,” precisely because the cardinal is in such poor health. The greater the time to the trial, they argued, the greater chance Bevilacqua’s health would further deteriorate.

Sarmina then set Monday as the date she would hear arguments about Bevilacqua’s competency to testify, and she ordered lawyers to turn over the cardinal’s medical records by Aug. 22.

All attorneys in the case have been barred from discussing it publicly.

IN THE JUDGE’S INTEREST

Marci Hamilton, an attorney in several suits against Bevilacqua, Lynn and other archdiocesan figures, said Sarmina will be looking for the value of the cardinal’s testimony. The judge will listen to experts and examine records to determine if Bevilacqua can provide reliable evidence, Hamilton said. She’ll want to get a look at the cardinal, too, Hamilton said.

“She has to see how he talks and what he says,” Hamilton said. “The turning point is whether it is unfair to have him testify.”

The District Attorney’s Office began investigating Avery and Engelhardt in 2009 after the archdiocese notified authorities of complaints against the two men. Avery since has been defrocked.

Engelhardt, an Oblate of St. Francis DeSales, was accused of molesting a 10-year-old boy in the sacristy of St. Jerome’s Roman Catholic Church in Holme Circle in 1998 and ’99. The grand jury said Engelhardt then told Avery about the boy and that Avery began molesting the boy.

The victim, now an adult, was molested the next year by Shero, a lay teacher at St. Jerome’s parish school, the grand jury said.

The grand jurors said Lynn knew of previous allegations involving a minor and had ordered Avery to get therapy. The grand jury said Lynn ignored recommendations that Avery not be trusted around children and had him assigned to St. Jerome.

During the course of the probe, investigators started looking into allegations that Brennan had molested a Chester County boy in 1996. The grand jurors said Lynn knew of previous allegations against Brennan but had transferred him instead of keeping him away from children. Brennan was assigned to St. Jerome in 1997.

On Aug. 5, Sarmina said jury selection would begin Feb. 21, 2012, and the trial is set to begin on March 26.

ANOTHER ISSUE

Prosecutors said Bevilacqua, who is a lawyer, is represented by the same law firm that represents the archdiocese and that there was a potential for a conflict of interest. Sarmina said she also will hear arguments on that point on Monday.

Questions of conflict of interest are not new in this case. Lynn’s attorneys are being paid by the archdiocese, a point that concerned Common Pleas Court Judge Renee Cardwell Hughes. During a March hearing, the judge — who has since left the bench to head the local Red Cross — cautioned Lynn that “someone else whose interest might not always align with yours is paying your attorneys” and suggested to Lynn that there might be several conflicts. Lynn said he trusted his attorneys.

Bevilacqua is a defendant in five civil cases filed this year that involve allegations of sexual abuse by priests.

Two of those cases involve former Northeast Philadelphia residents who said they were molested by a priest at Our Lady of Calvary Church in Millbrook. Lynn is a defendant in those cases, too.

Phil Gaughan, of Delaware, filed suit as a John Doe in March, but during a news conference, he identified himself and said that he had been molested by the Rev. John E. Gillespie from 1994 to 1997. Gaughan was a teenager and sacristan of Our Lady of Calvary at the time.

Named in Gaughan’s suit were Cardinal Justin Rigali, who recently retired as the city’s archbishop; Bevilacqua, the previous archbishop; Lynn; and two other archdiocesan employees.

Gaughan alleged that the defendants maliciously engaged in a criminal conspiracy to endanger children by taking no actions against priests accused of molesting children and that the archdiocesan victim assistance coordinators took information from victims and shared them with the archdiocese and its attorneys after misleading the victims to believe that their discussions were confidential.

The suit alleged, as did a recent grand jury, that Lynn was fully aware of the sexual abuse by priests.

“There is no doubt Lynn talked to Bevilacqua about Gillespie,” said Hamilton, one of Gaughan’s attorneys.

Later in March, a man who said he was sexually abused by Gillespie before 1994 also sued the archdiocese.

In his suit, the plaintiff, identified as John Doe 168, said he was molested while an altar boy from 1988 through ’91 at Our Lady of Calvary.

In his suit, John Doe 168 also named Rigali, Bevilacqua, Karen Becker, the director of the Archdiocesan Office of Child and Youth Protection; and Maggie Marshall, the archdiocese’s victims assistance coordinator.

The question of Bevilacqua’s competency as a witness could have some impact on the civil cases, Hamilton said. Whether the cardinal could be a witness in those cases might depend on how the criminal case goes, Hamilton said.

Rulings in the criminal case might not necessarily affect a civil trial, she said, but if the cardinal is not regarded as an acceptable witness in the criminal case, it would be strong evidence that he is not competent, and that issue would be relevant in the civil cases, she said. ••

Grand jury: Bevilacqua was a “difficult dilemma”

A Philadelphia grand jury looking into sexual abuse by clergy regarded Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua as a “difficult dilemma.”

Grand jurors wrote they believed the cardinal knew about the archdiocesan priests who molested children. Reluctantly, they decided not to charge him with endangering the welfare of children, although they did charge his secretary for clergy, Monsignor William Lynn.

They maintained Lynn endangered children by shielding two priests they said were molesters, and said “we would like to hold Cardinal Bevilacqua accountable as well” as Lynn. But they doubted Bevilacqua, who headed the city’s Roman Catholic archdiocese from 1988 to 2003, could be successfully tied to those cases.

They also wrote they were concerned about his health but not certain that what they had been told about Bevilacqua’s condition was believable.

“We have no doubt that his knowing and deliberate actions during his tenure as archbishop also endangered thousands of children in the Philadelphia archdiocese. Monsignor Lynn was carrying out the cardinal’s policies exactly as the cardinal directed,” grand jurors wrote.

Further …

“The cardinal’s top lawyer appeared before the grand jury and testified that the cardinal … suffers from dementia and cancer,” they wrote. “We are not entirely sure what to believe on that point. We do know, however, that, over the years, Cardinal Bevilacqua was kept closely advised of Monsignor Lynn’s activities and personally authorized many of them.”

Grand jurors wrote that Bevilacqua’s attorney, William Sasso, told them the cardinal’s doctors believe it would be “extremely traumatic” for the cardinal to testify before the grand jury and that any testimony he gave would be unreliable. ••