When soldiers return home from overseas, many have stories to tell.

But often, sharing those stories can be difficult. Sometimes soldiers have traumatic tales they’d rather try to forget than share.

Also, many veterans can become withdrawn because of symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), finding that simply communicating with others can be a difficult task that once was so natural.

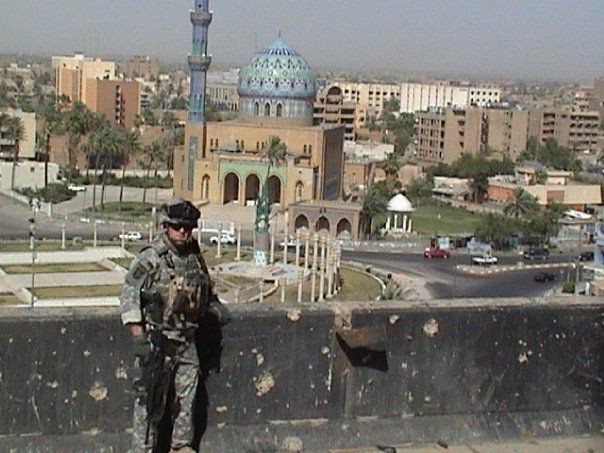

Sean Casey, a 30-year-old Doylestown resident and a veteran who spent five years with the U.S. Army — including tours of Iraq in 2006 and ’09, both through Baghdad — recalled that when he returned home he struggled with depression and was withdrawn to the point that he canceled get-togethers with friends and family.

“I called it ‘sitting in my shed.’ I’d tell people, ‘I’m going to be in my shed.’ Just making plans to meet friends would be difficult,” he said during a recent interview. “As a veteran, one of the common aspects of PTSD can be social isolation. It’s sort of a numbness . . . you just get to a point where everything is stressful.”

It’s a point where many veterans can become so isolated that they don’t know where to turn.

When Sean Casey stood at the crossroads, he learned of the local chapter of Warrior Writers, a nationwide non-profit association that provides creative outlets to veterans struggling with PTSD, and he soon found a sense of solace, he explained.

Casey — now the communications manager for Warrior Writers — said that in the military there are few chances for creative expression.

This program changed that.

It’s a creative outlet and an atmosphere of shared experience that Lovella Calica, 30, the founder and director of the program, said is proving successful for participants returning home from service in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Since the official start of Warrior Writers in 2007, she said, the group has served hundreds of veterans across the country by encouraging their involvement in writing, art or performance art. Calica, an artist and writer, had been working with veterans via other outreach projects before her development of this program.

The Warrior Writers organization is working on its third book of published works by veterans who’ve been part of the program.

ldquo;It started very organically. I just started sharing my poetry and they started sharing theirs,” said Calica, who lives in West Philadelphia. “When I started reading it, I was just so struck.”

The program has blossomed in its four years. Calica has taken Warrior Writers workshops to New York City and Chicago, among other cities, and she has found that veterans who join the program tend to encounter others with similar concerns or experiences, leading to special connections or bonds.

ldquo;I think it’s been really powerful for some people,” Calica said.

Casey thinks the program is important in urban areas like Philadelphia, where veterans can feel isolated from others as they rebuild their lives. Most military bases are in rural areas, he explained, and often there are more veterans and soldiers who settle down in areas near those bases to maintain that fraternal bond and support.

Urban regions, Casey said, are vast and move at a swift pace that can make veterans feel like outsiders. “Veterans in cities can kind of feel alone, or they’ll feel isolated,” he said.

Warrior Writers encourages a creative outlet to sort out those feelings. In addition to writing workshops, Calica said, the program brings veterans together by introducing them to a variety of artistic endeavors, thus enabling them to decide what they enjoy and how they want to create.

The workshops also can be a place where veterans simply stop by to listen to the poems or stories told by others, perhaps helping them to feel less alone for a while.

“Sometimes people do come to the workshops just to hear stories,” she said. “It’s a place they can come where people hear them and understand them.”

Although Calica has never served in the military, she has found a common bond with returning soldiers through creative expression. She considers the program an important tool that aids a veteran’s reintegration on the home front.

ldquo;I think our generation can do a better job of learning what it means to live among and with veterans so that veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan don’t become such a large part of the homeless population like our Vietnam veterans,” Calica said. “As citizens, we cannot just pass off responsibility to Veterans Affairs and wash our hands. We have an opportunity to move forward with all of our veterans, and change the ways we interact to create healthy relationships.”

Warrior Writers, she added, helps to indirectly treat soldiers who may have found little comfort in traditional therapy or have become lost through self-medication.

Casey agreed, saying the program doesn’t intend to replace traditional therapy for soldiers who need it, but exists as somewhat of a bridge for veterans to interact and express the feelings that returned home with them.

For Casey, Warrior Writers was the lifeline he needed. “Absolutely, this was instrumental in me getting my confidence back,” he said. “We aren’t trying to take the place of traditional therapy, but we are another tool in the toolbox.”

In her time working with veterans in Warrior Writers, Calica said, she has been inspired by their strength as they look to a happier future.

“It’s this ability to move forward, and that is something I feel affected by,” she said. “I’ve found community here in a way I never expected to.” ••

For more information on Warrior Writers, visit www.warriorwriters.org