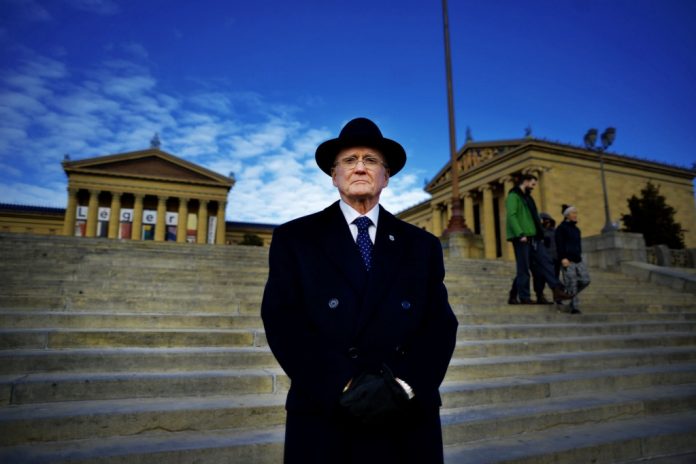

Philly’s finest: Jimmy Binns stands outside the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In December, he completed an 11-month certification course at the Delaware County police academy. He passed all the academic and physical tests, graduating first in his class with a 98.4 grade point average and won the Police Chiefs Award for his all-around performance and leadership. MARIA POUCHNIKOVA / TIMES PHOTOS

Nobody can accuse Jimmy Binns of failing to answer the bell.

Or, to borrow a line from his favorite fictitious Philadelphia fighter, Binns has never been mistaken for “just another bum from the neighborhood.”

The veteran litigator, former state boxing commissioner, sometime actor and recent suburban police academy graduate rarely has missed an opportunity to intensify his community engagement or amplify his celebrity since his days as a Pop Warner football star for the Mayfair Rams in the early 1950s.

Perhaps best known nowadays for his frequent public appearances advocating for the families of slain police officers and firefighters, Binns, 74, boasts an eclectic curriculum vitae that includes cameo appearances in two Rocky sequels. Neither role was a stretch. Filmmakers asked Binns to portray himself both times.

“I met Sylvester Stallone when I was a boxing commissioner,” Binns said during a recent interview. “I first met him at Bookbinder’s, and I used to see him out in Las Vegas at fights. He was making a new movie and asked me to act in it.”

Binns played an attorney in Rocky V in 1990 and a boxing commissioner in Rocky Balboa 16 years later.

“I had nice speaking parts in each,” he said.

Much like Stallone’s title character, Binns is walking proof of the heights to be achieved for an individual with charisma, knowledge and ambition, regardless of the neighborhood from which he comes.

“I’VE NEVER SEEN A FIGHTER THAT CONCERNED ABOUT HIS HAIR.”

That was how TV announcer Stu Nahan described the exceedingly self-absorbed Apollo Creed as the champ stepped into the ring for his first bout with Rocky Balboa. At first glance, a similar assessment seems apropos for Binns.

Regardless of the crowd, it’s impossible to miss his tall, svelte figure and meticulously crafted gentleman’s attire. His garb may include a pinstriped business suit or pleated slacks with offsetting blazer and tie. His shirts feature starched collars and French cuffs, often pastel in color and always freshly pressed. No ensemble is complete without wingtips or spats and perhaps a tan fedora.

Binns combs his white hair straight back and he is always cleanly shaved. A square jaw is his most pronounced feature and he knows it. So did world-renowned artist and illustrator Leroy Neiman when he sketched Binns’ profile years ago.

The attorney enthusiastically distributes miniature glossy reprints of the portrait on the front of his oversized business card. If you meet him once, you’ll be given a card. If you meet him a second time, you’ll likely get another. It probably won’t fit in your wallet, though. It’s too big.

Nonetheless, Binns’ self-evident narcissism is neither without merit, nor lacking purpose. It’s like his passport, granting him free travel among the often contradictory worlds of the criminal, the police officer, the boxer, the businessman, the Mayfair kid and the Main Line socialite.

“STAY IN SCHOOL. USE YOUR BRAIN… BE A THINKER, NOT A STINKER.”

Binns didn’t need Apollo Creed’s advice about the pitfalls of punches to the face or the advantages of education. He learned it firsthand.

Born Sept. 27, 1939, Binns spent the first 14 years of his life in Mayfair. His family lived at 3154 Unruh St., and he attended grade school at St. Timothy’s. He was a good student and athlete. His Mayfair Rams played home games at Wissinoming Park. In 1952, he made the all-city Pop Warner team.

“I played end, both ways of course,” Binns said.

In his early teens, the family moved to Mount Airy. He attended the old La Salle College High School at 20th and Olney and graduated in 1957. Four years later, he graduated from La Salle College magna cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in accounting. What would become his lifelong passion for boxing emerged in those undergraduate years.

“When I was in college, I decided I wanted to become a boxer. I met a classmate whose uncle managed fighters down in South Philadelphia at the Passyunk Gym,” Binns said.

The now-defunct training facility at Moore Street and Passyunk Avenue was home to a host of champion fighters back then, including Sonny Liston and Joey Giardello. Binns, a straight-A college student, showed up one day.

“I trained there and fought as an amateur for two years. I fought a lot of professionals in the gym there,” Binns said. “But after two years, I decided it was time to move on.”

Binns landed a cushy job with an accounting firm, but it didn’t last. Too boring.

“I decided I was too young to enter the workforce,” he said.

So he went back to college, riding an academic scholarship through Villanova Law School. Initially, he studied a lot of tax law, but the fighter in him won out and he began specializing in litigation. He was admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar in 1965 and within two years had opened his own firm.

“The first time I went to court was when I was sworn in and the second time I was picking a jury for a civil trial,” Binns said.

He still practices independently with offices at 18th and Market streets and is licensed in 20 states. He has been admitted to federal district and appeals courts, and is a member of the bar of the U.S. Supreme Court.

“FROM HERE ON IN, JUST LET ME DO THE FIGURIN’.”

Rocky wasn’t just a fighter. Sometimes, his loan-shark boss, Tony Gazzo, instructed him to break a few legs too. For Binns, defending similarly dubious characters against criminal charges is a part of his job description, but he made his bones elsewhere. The World Boxing Association, the oldest among boxing’s four major governing bodies, has retained his services in 34 cases involving many of the biggest names in the sport’s history.

In the late 1970s, Binns met bantamweight champ “Joltin” Jeff Chandler at the Juniper Gym in South Philly. Someone sued Chandler, so the WBA hired Binns to defend him. The governing body hired Binns again for a case involving lightweight champ Claude Noel.

Binns also has represented promoters in litigation and contract negotiations. He defended Don King against a claim filed by Mike Tyson’s attorneys and negotiated title bouts for Frank Bruno and Barry McGuigan.

Binns’ connections in the legal, boxing and political communities paved the way for his appointment to the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission in the 1980s.

“It’s all a matter of networking,” Binns said. “One thing leads to another. One door closes and two more open.”

“TO YOU IT’S THANKSGIVING. TO ME, IT’S THURSDAY.”

Rocky’s take on holidays was less than enthusiastic, but he’s not the only one for whom Thanksgiving, Christmas and Easter are double-edged swords.

Joy is always tempered with grief for the families of police and firefighters who’ve lost their lives protecting the city. For more than a decade, Binns has dedicated much of his time to helping those families cope with loss and preserve the legacies of their loved ones.

Each Easter, Thanksgiving and Christmas, he joins leaders of the Fraternal Order of Police and dozens of cops in delivering holiday meals to slain officers’ families. He is also founder of the Hero Plaque Program.

“That developed because I owned a restaurant in the year 2000 at 13th and Locust,” he said. “I got it through a lawsuit. I hated it but I had to go to it.”

A local police sergeant often stopped there while making his rounds.

“One morning, he pointed out the window and said, ‘The night Danny Faulkner got killed, he was laying right there,’ ” Binns said.

The attorney came up with an idea to honor the slain officer by installing a plaque on the very spot. He called Faulkner’s widow to ask her approval. Maureen Faulkner consented and promised to attend the dedication ceremony in 2001.

“She flew back from California and about one thousand cops showed up,” Binns said.

In 13 years, the program has been responsible for installing 261 police and firefighter plaques throughout the city and surrounding counties and the Jersey Shore. Binns, who no longer owns the restaurant, has developed deep personal ties with slain police and firefighters’ families as well as active cops. He fights inside and outside the courtroom for their benefit.

He chairs of the annual Hero Thrill Show, which raises scholarship money for the children of slain police and firefighters. After a prior organizer cancelled the show in 2005, Binns formed a committee to renew the event in 2006.

He also helps active cops by raising money for new Highway Patrol motorcycles and Mounted Unit vehicles. His involvement has allowed him unique access to the closely guarded law enforcement community.

As a 68-year-old, the Highway unit allowed him to participate in its motorcycle training course, the one designated for cops, not the public.

“I went through the course and earned my wings,” he said.

In December, he completed an 11-month training and certification course at the Delaware County police academy.

“It was something that just occurred to me that I should emulate these officers that we honor through these terrific programs,” Binns said.

By far the oldest ever participant in the program, he passed all the academic and physical tests, graduating first in his class with a 98.4 grade point average. He won the Police Chiefs Award for his all-around performance and leadership. Now he wants a new career.

“I’m going to achieve a position with a law enforcement agency, something that has to do with motorcycles,” Binns said.

If it brings him more fame, so be it.

“It is what it is,” he said. “I’m proud of the work that I’ve done for the people who serve the city of Philadelphia and I’m more proud that they count me as a friend.” ••

Jimmy Binns poses in front of the famed Rocky statue outside the Philadelphia Museum of Art. MARIA POUCHNIKOVA / TIMES PHOTO