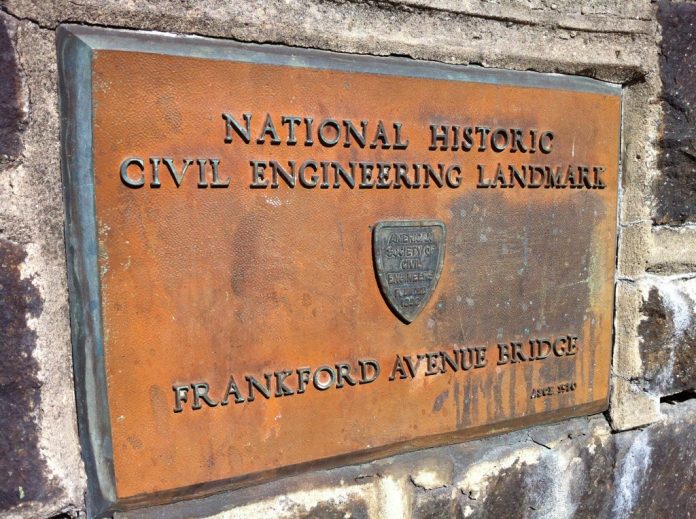

The Pennypack Creek Bridge, constructed in 1697, has been named a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark. PHOTO: WILLIAM KENNY

Pennsylvania has the second-most structurally deficient roadway bridges of any state in the nation, but the 319-year-old Pennypack Creek Bridge isn’t one of them.

Though designed and built a century before the Industrial Revolution, the 73-foot stone arch bridge remains fully functional for its original purpose. It conveys about 14,830 vehicles per day, a figure likely greater than the population of the entire Pennsylvania colony at the time of the bridge’s 1697 construction.

As such, the Pennypack Creek Bridge is considered the nation’s oldest roadway bridge in continuous use and is the site of a Pennsylvania Historical Marker. It has been declared a National Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers and been featured in an independent film chronicling the development of the King’s Highway, a colonial-era cart path that evolved into present-day Frankford Avenue.

With The King’s Highway documentary set for its citywide premiere on Dec. 6 at the Kimmel Center, the Northeast Times decided to investigate why the Pennypack Creek Bridge has endured while so many other Pennsylvania bridges seem to crumble to the test of time.

“It’s an engineering marvel, but it also has to do with just the way stuff happened,” said Fred Moore, a Northeast Philadelphia historian and longtime Pennypack Creek Bridge enthusiast.

Officials from the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, the agency that maintains the bridge, agree. For PennDOT District 6 Bridge Engineer Din Abazi, the craftsmanship, efficiency and simplicity of the design evoke one of the great wonders of the ancient world.

“The pyramids do the same thing for us. It’s definitely a marvel,” Abazi said. “Just think of transporting the stone to the site.”

In engineering parlance, the structure is known as a stone arch bridge, and it’s not as rare as one might think. In fact, Pennsylvania has one of the largest collections of stone arch bridges in the nation. In the five-county Philadelphia region alone, there are 124 of them that measure at least 20 feet in length.

“The department has made a concerted effort in the last ten years or so of preserving these,” said Gene Blaum, PennDOT District 6 spokesman.

Chuck Davies, who now serves as the assistant District 6 executive for design, was a bridge engineer a decade ago when PennDOT began taking inventory of all those historic bridges. Inspectors noted their locations, conditions and pressing maintenance needs.

“These bridges are really treasured structures in the community. They add to the historic nature,” Blaum said. “It’s for that reason that the department has made the effort to maintain the stone arch bridges that we have. They represent a type of building that we just don’t have today.”

Wikipedia identifies the Mycenaean Arkadiko bridge in Greece as perhaps the world’s oldest existing stone arch bridge. It dates to perhaps 1300 BC and is still in use by the local Peloponnesians.

According to Abazi, stone arch construction remained prevalent through the American colonial period and well into the 19th century. The industrial age brought new materials and methods, including iron and steel truss bridges, reinforced concrete and, by the mid-20th century, pre-pressed concrete.

The way stone arch bridges work is simple, but effective. They rely on their own weight to provide strength and stability. They require strong foundations and must remain constantly under compression.

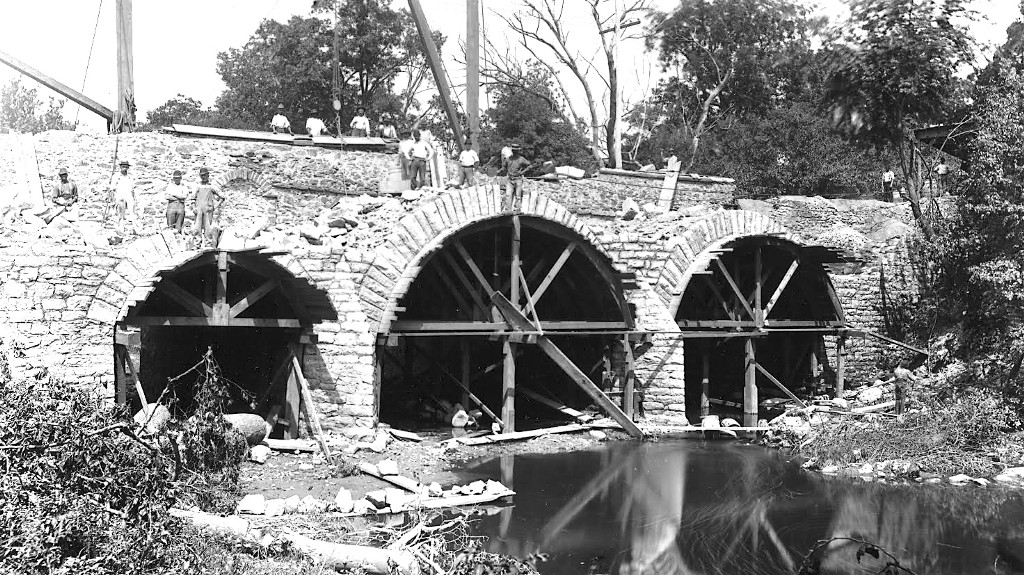

In constructing a stone arch bridge, builders first set up a false wooden frame to support the stones that comprise the arch. The top center stone, called the keystone, is the most critical because it keeps the rest of the stones in place. Once all the stones are in position, the framework can be removed. Additional stones are assembled to create the abutments and walls. Typically, builders use crushed stone to fill the gap between the walls and add vital weight to the structure. There is no deck to the bridge. The pavement sits atop the fill material.

Pennypack Creek Bridge has three original arches or spans. It was widened in 1893 to accommodate streetcars. The original arches are visible on the upstream side of the bridge. While photos of the expansion have survived more than a century and a quarter, the engineers can only imagine how resourceful the original constructors would have been to complete their project in a rural 17th-century setting.

“This type of construction is very labor intensive with a high degree of specialized craftsmanship in selecting stones from quarries and placement,” Davies said. “In many ways, it’s a lost art.

“It was a highly developed skill, something people carried around with themselves. It wasn’t so much technical specifications as their engineering knowledge.”

Stone arch bridges have advantages over more modern designs for durability. There is not metal to rust, although the freezing temperatures of winter can loosen and dislodge individual stones. Each year, PennDOT inspects each of its stone bridges after winter.

Pennypack Creek Bridge now rates as “fair” condition (a five on a zero-to-nine scale), although it is due for some rehab. Next year, PennDOT will issue a request for bids on restoration work with construction planned for 2018. And while physics hasn’t changed over the last three centuries, transportation demands and costs certainly have. Money seems to be one big reason public agencies aren’t building stone arch bridges today.

“It’s very labor intensive. It’s a very inefficient way (to build),” Davies said.

“The materials, the craftsmanship have to be there, and (lots of) time,” Abazi said.

Another strike against arch bridges is that under-clearance is limited by the length of the span.

Moore, the Northeast historian, has another theory for why Pennypack Creek Bridge has been able to survive. There was never a real need to replace it.

In the mid-1920s, Roosevelt Boulevard was built and diverted traffic from Frankford Avenue. Later that decade, public officials were planning to extend the Market-Frankford El to Rhawn Street in Holmesburg, which might have placed an additional traffic burden on the Pennypack crossing. But the Depression killed the El extension.

“That was one of the interesting things that didn’t happen,” Moore said.

In the 1960s, PennDOT built Interstate 95, which added another north-south traffic artery through Northeast Philly.

“It’s pretty obvious that Roosevelt Boulevard and then I-95 took a lot of traffic off of Frankford Avenue, although I have no proof of that.”

Moore notes that there are several other stone arch bridges in and around the Northeast. The Old Lincoln Highway bridge over the Poquessing Creek in Trevose was built in 1805, as was the Richlieu Road bridge also over the Poquessing. Both are closed to vehicle traffic. The Krewstown Road bridge over the Pennypack was also built in 1805, but its stone arches are shrouded in a concrete shell. In Mechanicsville, the Century Lane bridge over the Poquessing was completed in 1843 and remains in use.

But none come close to the Pennypack Creek Bridge on Frankford Avenue for its longevity, durability and usefulness. ••

Making history: A photo taken in 1893 shows the temporary wooden framework used to support the arches as workers widen the bridge. FRANKFORD HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Test of time: The 319-year-old Pennypack Creek Bridge, which conveys about 14,830 vehicles per day, is considered the nation’s oldest roadway bridge in continuous use. MARIA YOUNG / TIMES PHOTO