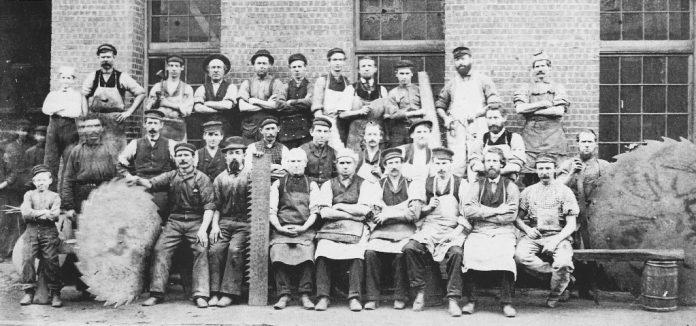

The pages of history: Disston sawmill workers in Tacony show their wares in the late 19th century. This photo is included in local historian Jack McCarthy’s new book, In the Cradle of Industry and Liberty: A History of Manufacturing in Philadelphia. PHOTO: HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF TACONY

Philadelphia has been called a lot of things throughout its history. Monikers like the Cradle of Liberty, the City of Brotherly Love and, perhaps less poetically, “Filthydelphia” have long captured the spirit of the metropolis with its nobility, passion and grit.

But perhaps no nickname encapsulates all of Philly’s enduring attributes, both distinguished and dubious, more than Workshop of the World.

A new book by Northeast-based historian, archivist and occasional Times contributor Jack McCarthy examines and contextualizes the city’s 330-year-old manufacturing legacy. It’s called In the Cradle of Industry and Liberty: A History of Manufacturing in Philadelphia. McCarthy authored the 100-page volume in 2014 and ’15 on behalf of the Manufacturing Alliance of Philadelphia. Former Mayor Michael Nutter contributed the forward. The Historical Publishing Network released it earlier this year.

It may be common knowledge that Philadelphia for much of its history has been world-renown for its industrial economy, a leading producer of goods large and small — from ships, locomotives and saws to textiles, lunch meats and beer. But McCarthy also explores Philadelphia’s manufacturing as a leading catalyst in the growth of the nation from its agrarian roots.

It’s a topic that should elicit interest from all sectors of society, the wealthy entrepreneurs and the working class.

“I think in Philadelphia the manufacturing history is so strong and widespread, almost everybody you talk to has a direct connection,” McCarthy said following his Dec. 7 lecture for the Northeast Philadelphia History Network. “People come up to me with their stories of those direct connections. So this subject resonates with a lot of people in Philadelphia.”

Indeed, no matter where you go within the city, longtime denizens are bound to share their personal remembrances of the good ol’ days when smokestacks ruled the skylines and family-sustaining employment was universal.

The true golden age of Philly manufacturing began around the same time as the nation’s 1876 centennial celebration and continued into the mid-20th century. At one time, Kensington was the heart of the city’s textile industry, the largest of its kind in the world. The neighborhood also boasted the world’s largest hat factory, Stetson.

In Tacony, Henry Disston built the largest saw works in the world with more than 4,000 employees at its peak and pioneered the concept of a company town. The Foerderer Leather Works of Frankford was considered the largest leather manufacturer in the world, while major breweries like Schmidt’s and Ortlieb’s called Northern Liberties home.

Matthias Baldwin established his state-of-the-art locomotive assembly plant at 19th and Hamilton streets in present-day Spring Garden. It would become the largest employer in city history with about 18,000 workers at its peak. Meanwhile, the Budd Company constructed railroad cars at 24th and Hunting Park, then later on Red Lion Road in the Far Northeast.

Philadelphia had leading sugar refineries in Fishtown (Sugar House) and Pennsport (Domino), the William Cramp & Sons shipyards in Kensington and Port Richmond, Midvale Steel in Nicetown and the Bromley Carpet mill in Kensington.

Of the men and women whose labors enabled these industries to thrive during the period, McCarthy in the book described them as a highly skilled, largely native and self-perpetuating workforce:

“It is difficult to generalize about a workforce that at the turn of the twentieth century numbered over a quarter of a million workers employed in thousands of establishments across the city,” the author wrote. “… The city never received the massive numbers of immigrants that New York City did, but the main determining factor was the nature of Philadelphia’s manufacturing environment: the specialty companies that dominated the industrial sector employed primarily highly skilled workers, offering the kind of jobs that were more likely to be learned over generations and passed down through families than made available to unskilled new arrivals.”

The book features five chronological chapters. The first few recount the origins of the city’s industrial economy during the Colonial and Revolutionary periods, as well as the “Athens of America” era of the late 18th century when Philadelphia was considered the “political, cultural and artistic capital of the United States,” McCarthy said. Between the Federal period and the Civil War, the city’s economy evolved from a mercantile dominant to a manufacturing one. Some of the earliest large industrial developments in the city included the U.S. Mint in 1792, the Schuylkill Arsenal in 1799, the Navy Yard in circa 1801 and the Frankford Arsenal in 1816.

“All of them lasted into the 20th century,” McCarthy said.

Philadelphia was positioned well as a hub of manufacturing. Raw materials came via river and rail from upstate. Anthracite coal from the Lehigh Valley powered the industrial revolution, while innovators like Oliver Evans, who developed the high-pressure steam engine here, invented machines that allowed for mass production. Further, Philadelphia’s port allowed companies to export their products around the world.

The dynamic changed in the latter 20th century as manufacturing gave way to service-based industries as the city’s economic driver, but Philadelphia continues to hold onto its heritage in many sectors such as transportation equipment, food processing, pharmaceuticals and oil refining.

McCarthy sees a lot of parallels between the city’s newest manufacturing initiatives and its past. The controversial energy hub effort would bring raw materials like natural gas to the city, where it would be refined and shipped abroad. Also, there is a growing grassroots-style sector known as the maker movement with craftsmen and artisans working on small scales to serve niche markets.

“It’s kind of like a return to the craftsmen of the colonial city,” the author said. ••

In the Cradle of Industry and Liberty is available in hardcover and softcover from the author via 215–824–1636 or j[email protected].

Historical developments: Jack McCarthy examines the city’s 330-year-old manufacturing legacy in his new book, In the Cradle of Industry and Liberty: A History of Manufacturing in Philadelphia. McCarthy is pictured above during a lecture on Dec. 7 for the Northeast Philadelphia History Network. MARIA YOUNG / TIMES PHOTO