High tech: Ryan Matson, 18, designed a prosthetic limb. MARIA YOUNG / TIMES PHOTO

The story of MaST Community Charter School’s ultra high-tech curriculum got legs in the local news media last winter after students used their three-dimensional printer to craft a paperweight-sized bust of Mayor Jim Kenney.

Since then, the Somerton-based K to 12 institution has elevated its game, as pupils have eschewed headline-grabbing gimmicks in favor of practical applications.

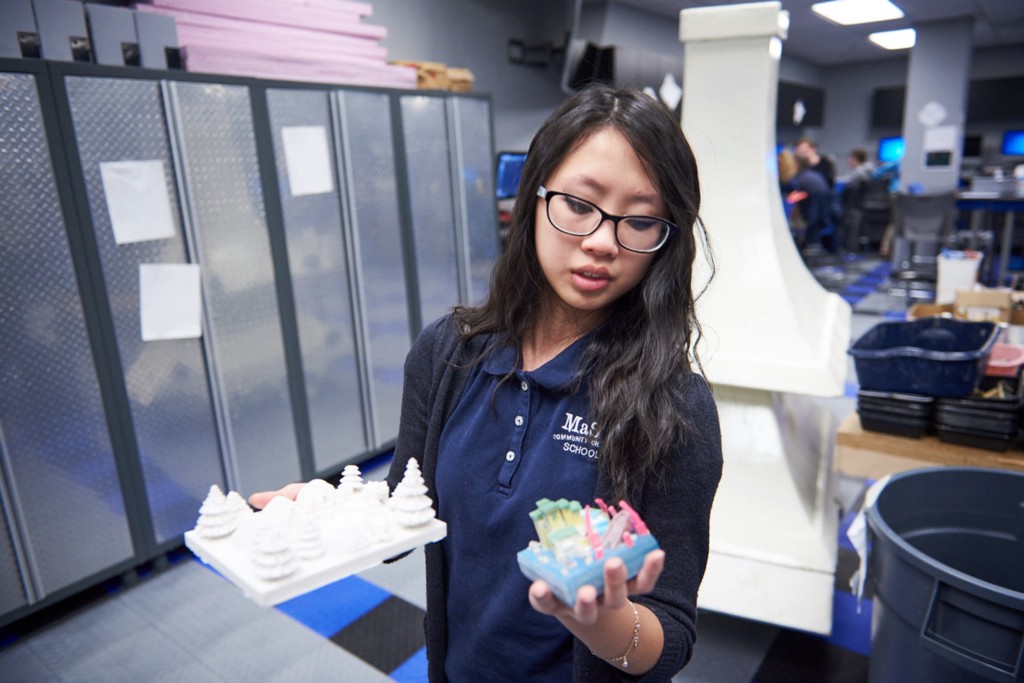

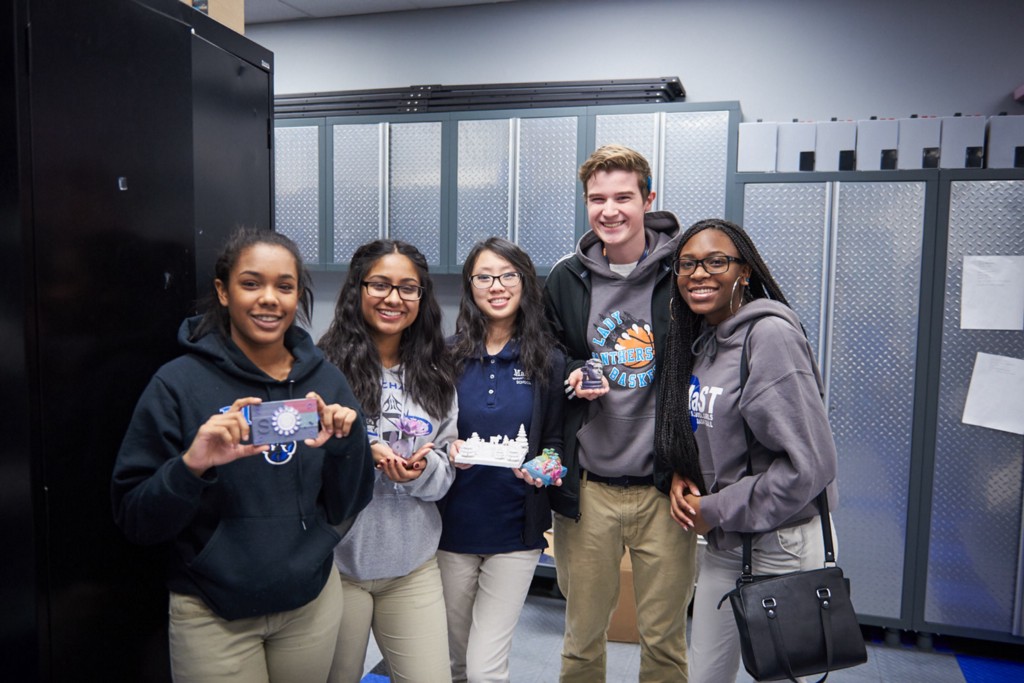

High school junior Dan Winter is using professional-level engineering software to design cooking utensils for carpal tunnel sufferers. His classmate, Max O’Donnell, is making a 3D jigsaw puzzle of the popular Pokemon character Pikachu. Serena Robinson, Amanda Ma and Megha Mathew — juniors all — are developing an equally marketable 3D version of the Candy Land board game that they meticulously assembled from some 10,000 virtual objects. Senior Ryan Matson designed several ornamental rings and a prosthetic leg.

The 3D design workshop is one centerpiece of the school’s cutting-edge “makerspace” lab, a facility that also houses crime scene-style forensics and robotics programs. The lab debuted in 2014 and was financed almost exclusively through fundraising. According to MaST CEO John Swoyer, student parents have generated $100,000 each of the last three years to augment the school’s public funding allotments.

The result has been an elite technology curriculum, the level of which can be rarely seen in an urban public school setting.

“The concepts they’re working on are more college-level, more elaborate,” Swoyer said. “They’re engineering real-life products, (such as) shoes, light bulbs, lamps, chairs, class rings. We first brought in the 3D printer about three or four years ago. Back then, it was about learning its capability, what the printer could do. But now it’s about learning what the students can do, what they can design.”

Teaching technology has always been an emphasis at MaST since its 1999 founding. The name is an acronym for Math Science and Technology and was chosen soon after the federal government, through its National Science Foundation, had adopted another acronym, STEM, to represent its advocacy for enhanced science, technology, engineering and math instruction throughout the nation. MaST has since added robotics and arts to round out its unique “STREAM” curriculum.

“We’ve tried to make it more kid-centric, something that would appeal more to them and to colleges” for enrollment application purposes, Swoyer said.

MaST’s campus at 1800 E. Byberry Road has about 1,300 enrollees in all grades, including more than 400 in the high school programs. Those are the ones who make use of the makerspace, which has workstations and large-screen computer terminals arranged in a circular pattern conducive to collaboration among classmates and teachers.

The makerspace accommodates two classes of about 20 simultaneously, four times each school day. The technology and science departments make the most use of the facility. Students have access to product design I and II, engineering I and II, robotics and forensics. All are electives.

Teachers Sarah Sholette, Lena Mendes, Eric Tanner and Stacey Strayer comprise the school’s newly constituted technology department, while science teacher Sommer Pellecchia developed the new forensics class by expanding on her own popular lesson plan on the topic.

Central to all of the courses, they say, is an emphasis on the practical applications of the work. When Winter designed his ergonomically correct spatulas and serving spoons, he also had to conceive a marketing pitch.

“They’re called ‘Kitchen click-ons.’ I did a whole presentation to the class, Shark Tank-style,” Winter said, referring to the ABC television series for aspiring entrepreneurs.

Winter convinced his peers to invest $250,000 in his product in exchange for 10 percent equity in the company.

Matson’s prosthetic limb project was inspired by a Ted Talk video that Sholette played for the class. In the film, an MIT professor and double amputee discussed having designed his own bionic legs.

“We watched that first and all of the students incorporated that into their own designs,” Sholette said.

Matson learned a lot about the design software during the three-week project, as well as the human form.

“The toes, they were hard to do,” he said.

“It’s very complicated software and their ability to pick it up is a testament to their generation and the climate in school,” Sholette said. ••

Meet the makers: Mikayla Smith, Amy Heineman and Rosalee Schemaitat do forensic schoolwork in the school’s “makerspace” lab. MARIA YOUNG / TIMES PHOTO

Meet the makers: MaST students (top photo, from left) Serena Robinson, 16, Meghan Mathew, 16, Amanda Ma, 17, Maxwell O’Donnell, 16, and Ashe Raifa, 17, hold their 3D designs. MARIA YOUNG / TIMES PHOTO