A former reporter recounts a time his father had a chance encounter with Jim Bunning, former Phillies pitcher.

By Joe Devine

Like most Phillies fans over the past half-century-and-a decade, my initial thoughts and images of Jim Bunning go directly back to Father’s Day 1964.

I was introduced to the Phils’ dogged righthander by his unforgettable memory of pounding his hand into glove, seconds after striking out New York Mets pinch-hitter John Stevenson to complete his stirring perfect game — the first perfect game in Major League Baseball’s regular season since the 1920s, and the first in the National League since 1880.

But my memories go a little deeper than those shared by millions of others. And it’s because of my hero — my dad. My dad, Bill Devine, had a chance encounter and meeting with Bunning, the Phillies’ Hall of Fame righthander who died May 26 at the age of 85. Just two matter-of-fact guys from big, Depression-era families, guys who were straight shooters who weren’t afraid to speak their mind and stick their necks out for their friends, coworkers and, yes, teammates. Guys who prided themselves most on being good family men and great fathers, working hard and loving their family, friends and God.

This chance encounter needs some setting up before it gets to spring out at you like one of Bunning’s impossible-to-hit sliders in the dirt. My dad grew up in the coal-mining, picturesque town of Pottsville, set in the beautiful mountains of central Pennsylvania. Pottsville has become known best for the Yuengling Brewery — the oldest brewery in the country (opened in 1829), and for being the birthplace of legendary coal-mining labor union giant John Lewis and renowned author John O’Hara. It is also known for the Molly Maguires. the Schuylkill County Courthouse, the Coney Island Restaurant, the “Indian Head” stone marker upon entering the town, St. Patrick’s Church and for the Pottsville Maroons, quite possibly the greatest team in NFL history.

Yes, NFL history. The Maroons overwhelmed everyone in America in rolling to the 1925 NFL title, crunching teams like the Green Bay Packers, Chicago Bears, New York Giants and Chicago Cardinals in the process of winning the world championship of football. Blew out the Cardinals on their home field in the championship game.

But don’t bother looking up the details of that one in the official record books. The Maroons had their title stripped from them because they played — and defeated — the legendary Notre Dame Fighting Irish, manned by the Four Horsemen and coached by Knute Rockne in what was billed as the “Game of the Century.” The Maroons needed the money from the game to stay afloat financially, so they played the “exhibition game” in Philly. Since the NFL had not sanctioned the game, it retaliated by taking the title away from Pottsville and awarding it to the very Cardinal team the Maroons had blown out two weeks earlier. There apparently were Roger Goodells back in the Roaring ’20s, too. Don’t let any good Pottsville resident hear that the Maroons weren’t the real champs that storied season. The Cardinals and the Bidwill family are so scared of invoking Pottsville’s ire that they have run all the way to Arizona to get away from it.

So my dad grew up learning how to scrap and how to share. Such is life when one grows up in a cramped little house on the wrong side of the tracks, with eight boys and a girl sharing two rooms. The Devine boys squeezed two to a twin bed and got by on ketchup sandwiches and the love that only such a close-knit clan could elicit. It is rumored that the youngest of the boys (Greg) slept in the crib he had as a baby until he was 12 years old. Other similar, countless stories have been embellished through the years and through the beers that were drunk while telling them. But the fact remains that, to this day, I have never known a group of brothers who were ever closer or had more love for each other than “The Brothers.”

My dad grew up a Phillies and A’s fan in the late 1920s, which is where the Bunning connection starts to take shape. Dad’s favorite player was catcher Mickey Cochrane, the Hall of Fame A’s catcher who helped lead the A’s to three straight World Series titles from 1929–31. Beat a couple of fellows named Ruth and Gehrig (in their prime) in doing so.

But A’s owner Connie Mack started selling off the players one by one because of the dire financial straits the country was in (the stock market had collapsed just two years earlier). Cochrane went to the Detroit Tigers (the same Detroit Tigers whom Bunning spent the first nine years of his major league career with) in a straight cash deal, and my dad’s allegiances went with him to the Motor City. Cochrane’s first year with the Tigers in 1934 (and my dad’s first year following them) saw Detroit win the American League pennant before losing a seven-game World Series to the St. Louis Cardinals. The next year, the Tigers turned the trick on the Redbirds and won the World Series championship themselves. My dad turned all the Devine boys into lifelong Tigers fans except for his brother, Jack (a Cardinals fan because of Stan Musial).

One of my Dad’s earliest boyhood dreams was to someday be able to go to a spring training in Florida. After becoming a World War II hero (a bombardier on a classic B-24 Liberator plane who flew a couple of missions with Jimmy Stewart), dad’s crew flew 20 missions over Berlin, Austria, and most of the European theater. The missions included participating in the famed Ploesti oil raids that helped win the war. The crew was shot down over Vienna shortly before Christmas 1944. Dad saved another crewmate’s life as their plane was being shot down and crash landed himself after parachuting from the free-falling plane, breaking his ankle in the process. The village townspeople had been shooting at them like sitting ducks as they were coming down, and they chased the Americans with shotguns and pitchforks when they reached the ground. My dad had to run away on his broken ankle, pain throbbing unmercifully with each step he took.

Fortunately, before he was about to pass out from the pain, the Germans surrounded the crew and took them as POWs. Dad had to walk 20 miles on a broken ankle with a makeshift crutch before being shuttled in a cattle car to Stalag I, where he spent the remaining six months of the war. The compound was eventually liberated by Gen. Patton’s army in the waning days of the war in 1945, with dad earning a Purple Heart and Silver Star for his efforts.

There was little to keep the fellas’ hopes and spirits up in the cruel harsh realities of POW camp. My dad kept going by dreaming of our mom (who had promised to wait for him when they left each other at the train station as sweethearts in 1942), the brothers, the slice of heaven that was Pottsville, and a repeat title for the Detroit Tigers in the fall of 1945. Detroit had won the 1944 World Series with a nucleus that included pitcher Hal Newhouser (a 29-game winner), Hank Greenberg and my dad’s newest favorite player — second baseman Charlie Gehringer. All three became Hall of Famers.

After my dad was reunited with his family and our mom in the spring of 1945, the Tigers did indeed go on to win the World Series over the Chicago Cubs (the Cubs’ last appearance in the Fall Classic before last season’s title). After being married and raising us five kids and working his way up from a knitter in a small textile mill to the company’s vice president, dad figured it was time to cash his check on the spring training dream he had as a kid. So in the spring of 1974, he took a train to Clearwater, Florida, on a whim and set out to share a week of blissful baseball and sand beaches.

The Phillies were in a definite transition at that time, having endured a decade of pathetic losing after their ill-fated 1964 collapse in the pennant race. As he called home each night, he marveled at the promising young talents being assembled for early morning workouts and the afternoon Grapefruit League games. He particularly raved about a young third baseman who came off a rookie season in which he had hit just .196.

“This young kid at third looks like he’s gonna be a Hall of Famer some day,” dad said one night. “The best fielding third baseman I’ve ever seen. Looks like he could have some pop in his bat, too. I hope they give him a chance this year, ’cause he looks like he could be something special. Nobody really knows who he is, though, but I think he’s going to be great!”

Some 548 homers, 13 Gold Gloves and three MVP awards later, people came to know the name of Michael Jack Schmidt. But my dad’s amateur scouting reports weren’t perfect, either. He also saw a lot of promise in Mike Anderson. He was, after all, only human.

One night after a day of watching early morning workouts, followed by a stint at the beautiful Clearwater beach and an afternoon Grapefruit League game against, yes, the Detroit Tigers and our all-time, ALL-TIME favorite Tiger, Al Kaline, who was entering his 20th and final season, my dad sat down to dinner at the small but quaint little restaurant around the corner from Jack Russell Stadium.

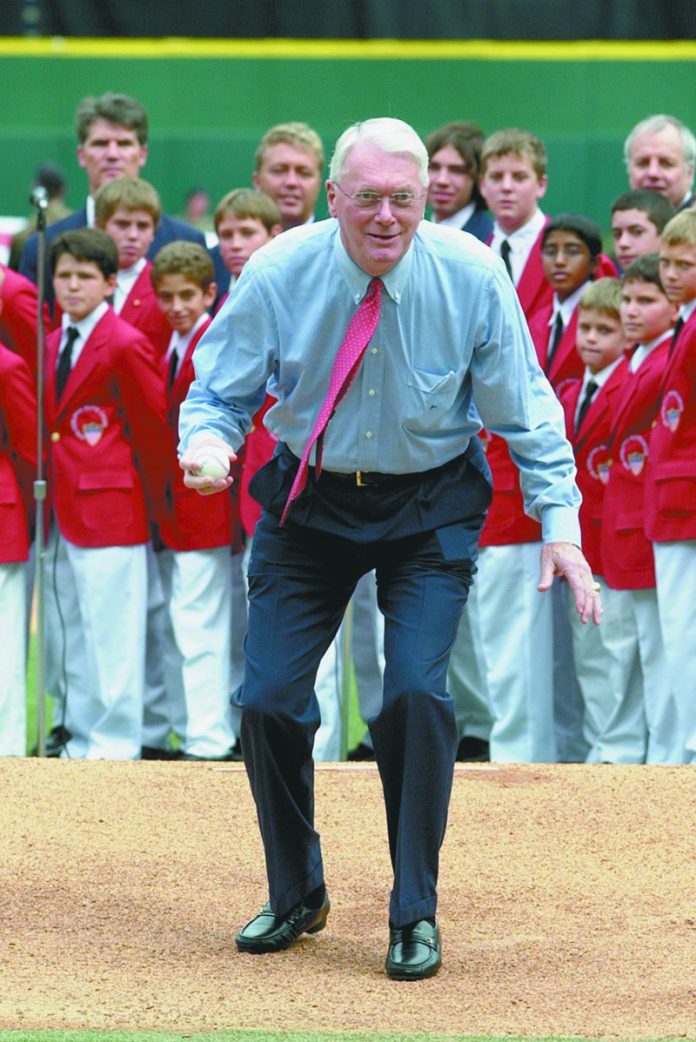

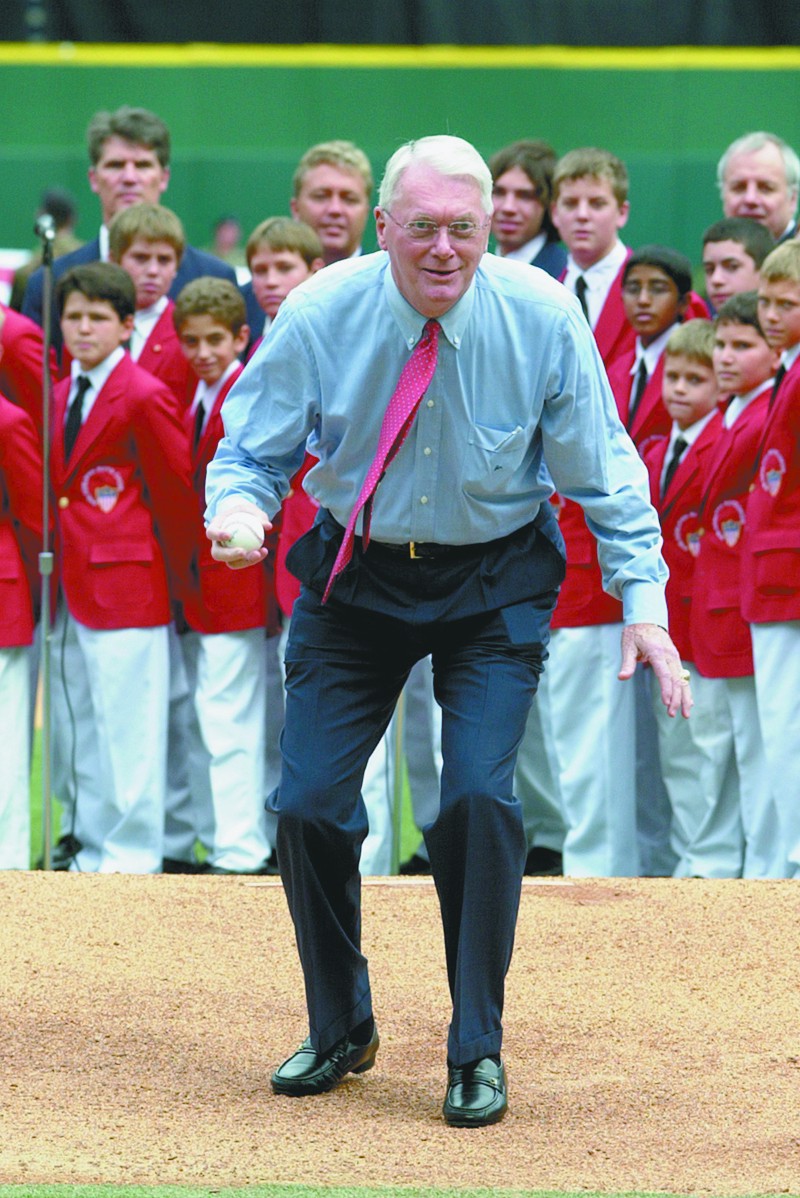

Since it was “Phillies Week,” (the Phils were home all week in a nice bit of timing by the schedule makers), the joint was jumping all week with patrons, with no seat or table to be found. Dad had just nabbed the last table and was glancing at the menu when a tall, handsome fellow walked in and requested a table because he was in quite a bit of a hurry. Dad recognized right away that it was one of his old favorites, Jim Bunning.

“Mr. Bunning, it will be probably be quite a wait,” the exasperated young hostess said to him. “You might want to try another restaurant rather than staying here.”

Dad would have no part of that. He calmly went over and said, “Jim, I’m a huge fan and have a table to myself along the side of the wall here. You would be more than welcome to join me for dinner if you don’t mind eating with a stranger.”

Bunning quickly accepted dad’s invitation. The two gentlemen formed an impromptu bond and mutual admiration society with each other at the table along the wall. They talked baseball and about life. They shared stories of both growing up during the Depression in a family of nine kids — Bunning in the small Kentucky town of Covington, just across the Ohio River from Cincinnati, and my dad, of course, in his beloved Pottsville.

They talked about being proud fathers and expectant grandfathers. My dad was “expecting” his first grandchild later that year. Bunning went on to eventually have 35 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren.

They talked about fighting for the underdog. Bunning was one of the first major leaguers to fight for a strong players union (he was the player representative for both the Tigers and the Phils) and helped get Marvin Miller elected as the powerful union negotiator that changed players’ salaries and the game forever. Dad had tirelessly fought for rights of common knitters in the textile mills in Philly, standing up to the ranks of company owners and presidents for his coworkers’ rights to better wages and working conditions.

Bunning helped establish simple but key rights as players having parking spaces at Connie Mack Stadium and wives getting to go on road trips before tackling the bigger things like pensions and player movement from team to team.

They talked about baseball some more. About Al Kaline, Bunning’s trusted friend and teammate for nine seasons in Detroit who was soon to collect his 3,000th hit.

They talked about the Tigers’ amazing comeback from a three-games-to-one deficit to defeat the favored Cardinals once again in the 1968 World Series (Uncle Jack wasn’t crazy about that) and Denny McLain and his 31 wins and about this good-looking young kid named Schmidt, whom Bunning had managed just a few years earlier at Reading.They talked about the potential of his other players he managed down on the farm, guys like Boone and Luzinski and a squirt of a kid with a temper but character named Bowa.

They talked more about life, about their devout Catholic backgrounds, the link to “St. Pat’s” (on the day Bunning pitched his perfect game in New York, he attended morning Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral). Dad countered by telling how HIS St. Pat’s was built next door to the Yuengling Brewery, which was built into the side of a mountain and gave it that extra cold, refreshing taste. Appropriate talk for two Catholics who were sharing a couple of cold beers while they were talking.

They even managed to talk briefly about the last week of the ’64 pennant race, when manager Gene Mauch panicked and twice used Bunning and Chris Short on two days rest, and in effect, blew the pennant. Bunning preferred to talk about how he was able to land a spot on the Ed Sullivan Show the night he pitched his perfect game in New York. Dad graciously let him go ahead and do so.

When the two got up to leave for the evening after two spirited hours of conversation, dinner and beer, they exchanged handshakes and well wishes. No iPhones or email addresses to exchange back in 1974.

Bunning was looking forward to a successful ’74 season at Reading and never gave any hint of becoming a six-term congressman or U.S. senator. Dad was looking forward to another couple of days of R & R and returning home to his loving family with a trunk load of stories and memories.

Ten weeks after our dad passed away in 1995, Jim Bunning was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. That seemed appropriate to us. He became the first person ever to be a Baseball Hall member and a member of the U.S. House and the Senate.

Besides his startling footnotes of becoming the first player to pitch no-hitters in both leagues (he tossed one for Detroit in 1958, against the Boston Red Sox, recording the last out against Ted Williams) and being second on the all-time list of strikeouts behind only Walter Johnson at the time he retired, Bunning is famously known in Philly circles as losing more 1–0 games than any other pitcher in history and recording the most 19-win seasons ever. He is one of only five Phillies players to have his number retired.

When Bunning walked into a crowded heaven on May 26, looking for a table, I couldn’t help but think that my dad approached him once more and asked him to join him for dinner. And the two brief-but-special friends talked baseball, family and life once more. ••

Joe Devine is a former Northeast Times reporter.