Vital information about Pennsylvania’s new medical marijuana program, including two Northeast Philly dispensaries, remains hidden from the public.

If you’ve ever heard or uttered the words, “Sunlight is the best disinfectant,” you’ll probably be glad to know its origins are as authoritative as authoritative can be.

The common adage was paraphrased from a line in a 1914 book of essays authored by Louis Brandeis, who would later become a U.S. Supreme Court justice. Brandeis wrote: “Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman.”

But in administering Pennsylvania’s new medical marijuana program, the state’s Department of Health seems to have adopted the opposite philosophy for protecting it from potential harm. Secrecy was a practice and policy of the health department and many of its licensees throughout the recently concluded first phase of licensing.

The state received 457 applications for permits to grow and process or to dispense marijuana leading up to its March 20 deadline. The health department created a panel of state employees to score the applications on a 1,000-point formula. But the department did not reveal the panelists’ identities — and has said it will not reveal them — to shield them from potential partisan influence. The state hasn’t even disclosed how many panelists there are or their expertise.

On June 20, the department awarded the first 12 grower/processor licenses to applicants across the state. Nine days later, it awarded the first 27 dispensary licenses, including two in Northeast Philadelphia and five more within five miles of the Northeast. Together, those seven account for more than one-fourth of all dispensary licenses awarded statewide. Both lists are posted on the health department’s website. The state expects dispensaries to begin operations next year.

Residents of the Bustleton and Parkwood sections were shocked to learn of the anonymous panel’s decisions. There were no public meetings in those communities about specific applications. Applicants were not required to brief neighbors on their plans. In Bustleton, one applicant contacted the local civic group but didn’t reveal where his company wanted to open a dispensary. In the Parkwood site’s case, the applicant didn’t contact leaders of the local civic association at all.

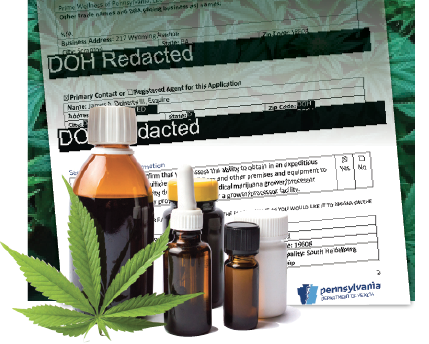

Soon after the dispensary sites were announced, the health department posted the winning companies’ applications on its public website. But folks seeking to glean more information about the licensees via those dozens of 240-page documents were sorely disappointed to learn that much of the potentially vital and locally relevant information had been redacted — blacked out — from the volumes of paperwork.

“A lot of people were calling me and knocking on my door after this came out that a dispensary was going to be at Franklin Mills,” said John DelRicci, vice president of the Parkwood Civic Association. “They had a lot of questions and I couldn’t answer the questions.

“They’re really concerned and upset about what kind of traffic this is going to bring in and what type of people. And they’re concerned how the community is going to turn. Is this going to be a good thing or a bad thing? They were very upset with this company coming in with no transparency, no communications with the residents.”

State lawmakers who created and legislated the Medical Marijuana Act of 2016 have been treated no differently. Rep. Martina White, whose district includes the planned site of one licensed dispensary, said she is among several House members who have contacted the Health Department seeking information about licensees and the evaluation process. White is still awaiting a response.

“The bill has stated that it’s a public record, that the information will be shared with the public,” White said. “The bill also says that applications will be subject to the Right to Know Law. … I would say the purpose of the bill was to make the process as smooth as possible with public transparency while protecting the integrity of the process and sensitive information.”

Those who want to read the act can do so on the Department of Health’s website. The law includes 21 chapters and 89 sections.

Illinois-based PharmaCann Penn LLC won a license to open a dispensary at 599 Franklin Mills Circle, a vacant commercial property once occupied by a Chi Chi’s restaurant on the perimeter of Philadelphia Mills. Unlike other licensees, PharmaCann sought to open only the one location. State law allows for licensees to operate up to three dispensaries in separate counties.

In Bustleton, Haverford Township-based Holistic Pharma LLC was awarded a license to operate a primary dispensary at 8900 Krewstown Road, as well as secondary dispensaries in West Norriton, Montgomery County and Bensalem Township, Bucks County. The Bensalem site is 4201 Neshaminy Blvd., 4.3 miles driving distance from the Philadelphia Mills site.

According to health department spokeswoman April Hutcheson, there was no explicit requirement for applicants to notify or meet with community groups during the application process, although “community impact” was considered by the panel in scoring all applications. The community impact category accounted for one-10th of the 1,000-point formula. Holistic Pharma scored 57.5 in the category, while PharmaCann scored 62.5. The state has refused to disclose how the panel arrived at those point totals for individual applicants.

Hutcheson said applicants were required to submit a document or letter from the local zoning authority stating a marijuana dispensary is a legal use for the location identified in the application.

The Krewstown Road and Franklin Mills Circle sites are both zoned for commercial use already. So under Philadelphia’s code, the dispensaries are permitted under the code as a matter of right.

According to City Councilman Brian O’Neill, when it became clear that Harrisburg lawmakers were going to pass a medical marijuana bill, Council passed an ordinance defining growing and processing businesses as well as dispensaries as commercial activities. Council also modified the city’s location restrictions to agree with superseding state law. For example, marijuana facilities cannot be within 1,000 feet of a school or child daycare center.

About a dozen constituents have contacted O’Neill’s office to lodge complaints since the health department announced the dispensary sites. Typically, he doesn’t hear from people when they support a new business so he’s not sure if there’s a consensus. People who want to learn more about the Bustleton site and the program in general can attend a meeting at American Heritage Federal Credit Union, 2060 Red Lion Road, on Wednesday, July 26, at 7 p.m. A physician and executive from Holistic Pharma are scheduled to address neighbors.

As for extensive redactions seen in most of the posted applications, Hutcheson said the applicants did most of the censoring. As part of the process, they were instructed to submit a completed application and a self-redacted application simultaneously before the March 20 deadline.

Applicants were instructed to redact anything that would be classified private under the state’s Right to Know Law, such as Social Security numbers, home addresses, personal telephone numbers and bank information, for executives and employees. They were also instructed to redact information regarding site security plans and anything they considered proprietary, the health department spokeswoman said.

In turn, the department reviewed the redacted applications to ensure that anything that should have been censored was indeed blacked out.

The companies’ interpretations of the instructions ran the gamut. Holistic Pharma blacked out very little from the public version of its application, only for the health department to redact dozens of entire pages. Meanwhile, some companies did most of their own redactions, leaving very little to the state.

In one instance, a company that ultimately won a license in Reading, Berks County, chose to redact the name and address of its proposed dispensary as well as the street address and state of the company’s headquarters in Arizona. The company redacted information about public access and transportation to the dispensary, its corporate training processes, its diversity plan and its maternity leave policy, among many other topics.

“I suspect that most applicants were over-cautious with their redactions,” said Jeremy Unruh, the general counsel for PharmaCann.

In a relatively new, highly regulated, highly competitive and lucrative medical marijuana industry, companies want to shield everything they do from the competition, including the way they prepare their applications.

“The ability to write an application is in itself valuable to the extent that (other companies) can take information that we’ve learned and developed over years,” Unruh said. “Even the level of granular detail among applications is a competitive advantage.”

Hutcheson said the health department cannot “unredact” any information that an applicant chose to censor. Folks who think they should have access to that information, particularly when it concerns a specific company that was approved to operate in a certain neighborhood, have recourse, according to the spokeswoman. They can contact the state’s Office of Open Records and file a Right to Know complaint. ••

William Kenny can be reached at 215–354–3031 or [email protected]. Follow the Times on Twitter @NETimesOfficial.