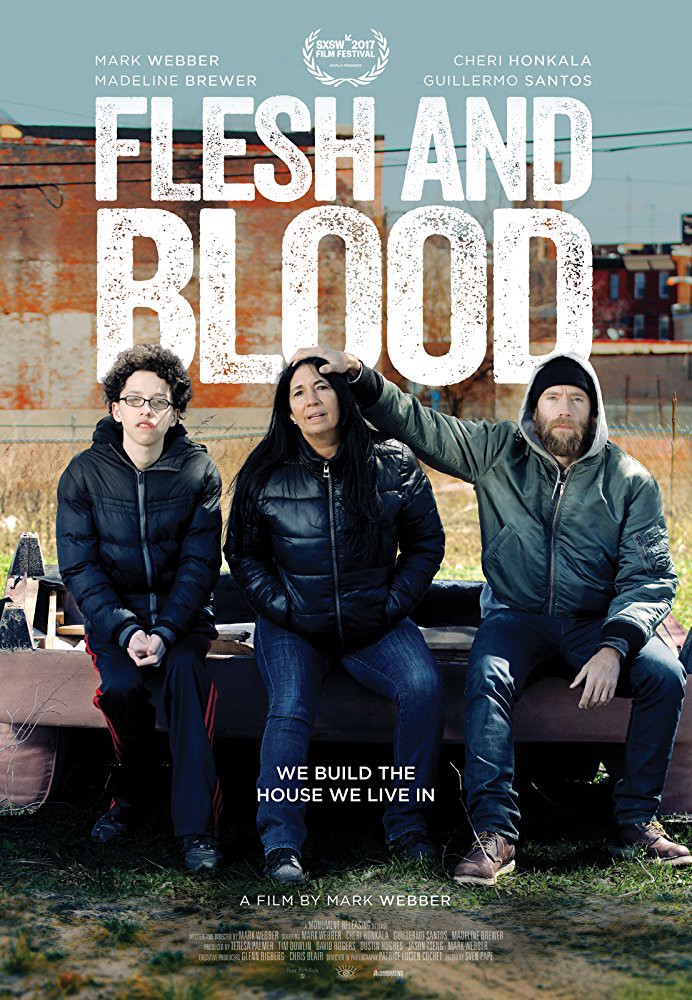

In Mark Webber’s fourth directorial project, he and his real life mother and brother film a semi-fictional version of their lives to staggering results.

Mark Webber, Cheri Honkala and Guillermo Santos are a family. Webber is a filmmaker, Honkala is an activist and former vice president candidate, and Guillermo is young kid dealing with a diagnosis for Asperger syndrome who is following in his brother’s footsteps with a handheld camera.

This is true in real life, and in the movie Flesh and Blood. Webber wrote, directed and acted the semi-autobiographical film, which tackles numerous storylines the North Philadelphia family has faced, and still faces today.

The movie begins with Webber being released from prison and moving back in with his mother and brother. This much is fictionalized — Webber described it as symbolic of his past.

There’s a vague subplot about Webber trying to outrun his crime-riddled past that passes by with a half-hearted wheeze, presumably due to its fictionalized roots.

The true strength of the film lies in its realness. It’s hard to commend the three performers for their acting, since they’re living or reliving real experiences.

But it’s easy to commend them each for the humanity they display on screen. Webber describes the film as “hyper realistic,” and the description is accurate.

There’s rarely a sense we’re watching actors reading lines (some scenes jump out as unrealistic when placed side-by-side scenes that are clearly real). The sheer honesty and trust the family imparts with the viewer is what takes it from being a movie to a fly-on-the-wall experience.

Webber is experienced behind the camera — this is his fourth directorial endeavor, and he’s acted in dozens of movies since 1998. This is a work only a skilled filmmaker and dedicated family man could produce.

After this project, Guillermo following in his brother’s footsteps seems inevitable. Webber buys him a handheld camera so he can start recording (his passions are video games, comic books, and movies).

The film includes multiple cuts filmed by Guillermo using that camera. The young scene stealer is a firework display on screen. As it turns out, it’s possible to be a scene stealer in real life.

The hyper realism of the move is something explored only lightly on film so far, which makes the novelty of this film linger. Webber’s formatting yields some awkward bumps in the road — both Honkala and Guillermo give long-winded expository introductions to get viewers up to speed. It’s clunky, but perhaps a necessity when we’re being introduced to people, not characters, in a movie’s limited runtime.

In an age where publicizing life events on social media is generally accepted as the norm, the film seems like the ultimate millennial achievement in oversharing. But, unlike a cluttered Facebook feed, the film is imbued with purpose. Webber and his family have a firm understanding of themselves (at least, the version portrayed here). There is catharsis in every scene because Webber did not shy away from tackling the family’s and his own demons.

Near the close, he meets his biological father (in the movie for the first time, in real life just the second). The encounter is scorching; his father is nearing the end of his life from complex health issues, and they mutually realize the time they will never spend together. (His father left Honkala and, according to her, never gave a dollar to help.)

Capturing a moment like that on film is weirdly exhibitionist, but wildly introspective, and it’s what helps Webber understand and recover.

In an odd, vicarious, but ultimately comforting way, the audience does, too. ••