Every fan of The Office is familiar with the scene where the sitcom characters are receiving a presentation and told to press a mannequin’s chest to the beat of the Bee Gees’ hit Stayin’ Alive. While in the show it’s played for laughs, in real life, that piece of knowledge could help you save a life.

CORA Services continued its community conversation series “kNOw Drugs in the Northeast” with its third conversation, hosted by state Rep. Joe Hohenstein at the Bridesburg Recreation Center. The conversation included Narcan kit distribution, along with demonstrations about how to properly administer the overdose-reversing treatment.

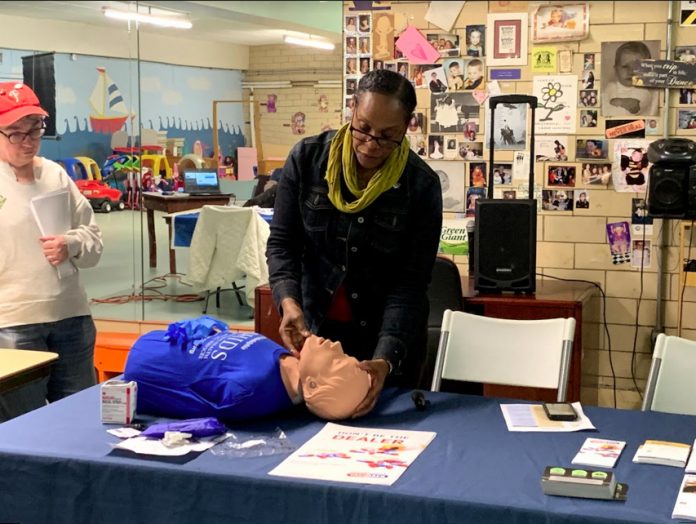

David Fialko of the Council of Southeast Pennsylvania Inc. and Pamela McClenton of the Department of Behavioral Health gave presentations on how to administer Narcan, a brand of naloxone, and the effects it has on a person experiencing an overdose.

Narcan comes in a white plastic bottle shaped like a lowercase ‘m’ with a nozzle pointing out of the top middle. Narcan can be picked up at any pharmacy over the counter with no prescription. If the pharmacy does not have any in stock, it should be able to get some within 24 hours.

Someone experiencing an overdose may have blue, pale or clammy skin, slow or no pulse, shortness of breath with a raspy voice, dilated pupils and may be nodding in and out of consciousness.

The Good Samaritan Act provides legal protection for individuals attempting to help anyone in distress, but you cannot help someone who is conscious and says they do not want help. When you approach a person who looks like they may be experiencing an overdose, call their name or try to get their attention. If there’s no response, gently shake their shoulder, Fialko said.

“Once you determine they’re unresponsive to those two modes, call 911,” he said.

You should then administer the naloxone, with one push per nostril. After the first push, lay the person in the rescue position if at all possible. Put them on their side and place both hands beneath their head. If possible, bend the top leg at the knee to help hold them steady. Once the first dose is provided, wait two minutes if there is no breath or pulse, or three minutes if there is, and administer the second dose in the opposite nostril.

“If after three minutes they’re not breathing on their own, this is when you want to start doing rescue breathing,” McClenton said. This is where knowing Stayin’ Alive is helpful: Give two really hard breaths into their mouth, then one breath every five seconds, which can be easily remembered using the chorus of the song.

“I can hum that and know it’s time to give another breath,” McClenton said.

Narcan lasts in the blood for only 30 to 90 minutes, which in some cases can be longer than the overdose lasts. You should always remain with the person so you can tell emergency responders when the Narcan was distributed and into which nostril.

Hohenstein hosted the conversation because he found it important to the residents in his community.

“Through all the discussions that we’ve been having about the opioid crisis, we’ve been focusing on individuals living with addiction,” Hohenstein said at the beginning of the conversation. “We haven’t been able to get the focus shifted to our communities and our families, and that’s what I want to do.”

“If we reach our families and our children in time, then we avoid so many issues of addiction,” he added.

Hohenstein reiterated his stance that receiving 15 to 30 days of treatment is not enough time to expect the individual to be able to make a full recovery, as he told the Times previously.

“They take the doctors, the airline pilots, the police,” he said. “The treatment programs for those folks start with six to nine months of inpatient treatment programs, therapy for them, therapy for their families, and then continued testing and connections through the next three to five years of their life. That’s treatment, and that’s what everyone deserves.”

Hohenstein also noted that a directory of all places in the city offering medically assisted treatment is available in his office. The list was passed out to attendees at the meeting.

Mary Doherty, who helps organize the community series, presented statistics about addiction overdose in the city.

In 2015, the crisis cost $504 million in the United States, or about 2.8 percent of the GDP. Four years ago, 26,500 overdoses were reversed thanks to naloxone.

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017 overdose deaths break down to these numbers in Northeast Philadelphia ZIP codes; 30 in 19124, 34 in 19135, 30 in 19149, 31 in 19111, 31 in 19136, 30 in 19152, 19 in 19114, 19 in 19115, 30 in 19154 and four in 19116. That makes a total of 258 of the 1,217 overdose-related deaths that year taking place in the Northeast.

Fentanyl was involved in more than 80 percent of unintentional opioid-related deaths in 2017.

The city has not sat by idly. The Philadelphia Resilience Project was the city’s response when the mayor declared an emergency in 2018, which mobilized 35 city departments to work together to address the crisis. Among their accomplishments, they cleared tons of trash from the streets and created safe corridor routes to travel to and from schools, among many other initiatives.

Monthly overdose prevention training is given by the Department of Behavioral Health every third Wednesday from now until December 2019 at 801 Market St., seventh floor. Participants will learn how to recognize protocols for effectively administering naloxone and more. To register, visit DBHIDS_narcan.eventbrite.com or DBHIDS.org/opioid.