Wendell Young III lived quite the life.

Young grew up on Longshore Avenue in Mayfair, part of St. Matthew Parish. His dad worked at the Navy depot. His mom, Gladys, was a housewife.

Wendell Young II later became an insurance salesman for Metropolitan Life, with an office in the old Sears, and the family moved to Castor Avenue in Northwood.

While a student at North Catholic, Young III began working as a clerk at an Acme at Adams and Whitaker avenues for $1.10 an hour.

There was no telling at the time, but that job led to an amazing professional career.

Elected as head of the Retail Clerks Union Local 1357 at age 24. Democratic ward leader. Delegate to five Democratic national conventions. Pennsylvania chairman for Edmund Muskie’s 1972 presidential campaign. Philadelphia campaign manager for Democratic presidential nominee George McGovern that same year.

In all, he remained president of the union (later named United Food and Commercial Workers Local 1776 after a series of mergers) until 2005, succeeded by his son, Wendell IV, who remains the union boss today.

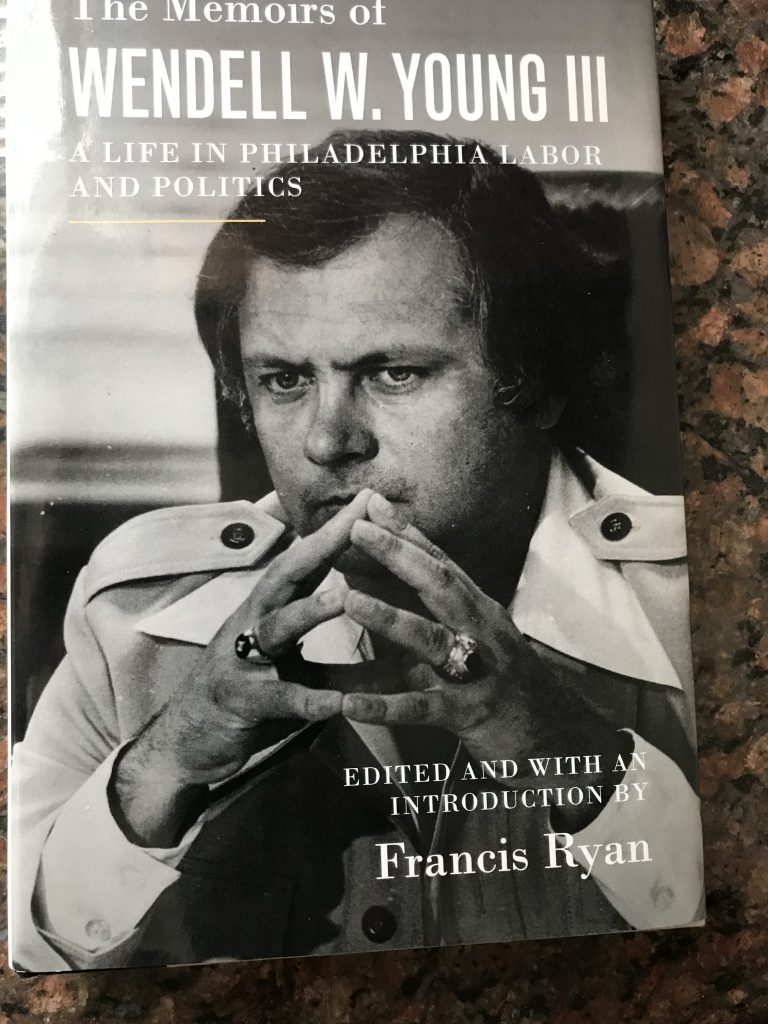

The Memoirs of Wendell W. Young III: A Life in Philadelphia Labor and Politics will be published on Monday.

Editor Francis Ryan, a Northeast natve and director of the Masters of Labor and Employment Relations program at Rutgers University, interviewed Young about his experiences.

There were 60 hours of interviews from 2009-12 at Young’s Lafayette Hill home. Young died of cancer in 2013 at age 74.

The book shows that Young was extremely liberal in the causes he championed and the candidates he backed. He opposed the Vietnam War, apartheid, nuclear proliferation and the invasion of Iraq. At the 1968 Democratic convention, he was the only Philadelphia delegate to back anti-war Eugene McCarthy over Hubert Humphrey.

The year 1960 was a big one for Young. He graduated from St. Joseph’s College, got married and moved into a Northwood apartment. He continued to work at Acme and taught social studies at North Catholic. He also was a local leader of John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign.

In that 1960 campaign, he worked to register Democrats in the 35th Ward, 26th Division, going up against Republican committeeman Eddie Becker (later a federal judge) and GOP ward leader John Kane (later a city elections commissioner).

Young took over the Retail Clerks Union in 1963.

In the book, he recalls a Local 1357 trip to Connie Mack Stadium in 1964. He and some union stewards were seated down the third-base line during a late-season game as the Phillies seemed to be closing in on the National League pennant and a trip to the World Series. In that game, Cincinnati’s Chico Ruiz stole home to give the Reds a 1-0 victory. The Phillies lost nine more games in a row and missed the chance to play in the World Series, and Young said members joked for years that they were a jinx.

Young had close ties to some fellow union leaders and clashed with a couple of others.

In the late 1960s, he, along with a young St. Hubert teacher named Rita Schwartz, battled with John Cardinal Krol to help form the Association of Catholic Teachers Local 1776. Schwartz remains president today.

Though a devout Catholic, he was from the social activism wing of the religion. A member of St. Martin of Tours, he was a lector who shared the altar one Sunday with Monsignor Walter A. Bower, who used his homily to criticize Cesar Chavez for leading a United Farm Workers boycott of grapes and lettuce.

Young genuflected and left the altar, angering Bower.

“How dare you do what you did out there,” Bower told him after the Mass in the sacristy. “That was an affront to this parish.”

Young did not back down.

“Don’t you dare talk about him like that as long as I’m on the altar, I’ll walk off every time.”

Young was also not a fan of Teamsters Local 115 boss Johnny Morris, as they were on different sides of a 1971 Lit Brothers strike and the 1992 Democratic presidential nomination fight. Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin was at a particularly raucous Philadelphia union meeting when Bill Clinton was nearing the ‘92 nomination, and remarked to Young, “I heard about the crazy fans here but I didn’t know the union guys were the same.”

Young thought it was time for local AFL-CIO head Ed Toohey to go, and was pleased to support Pat Eiding’s victorious 2002 campaign for the job.

Young had differing relationships with Philadelphia mayors.

In 1967, Mayor Jim Tate was reeling. He was not known as a great public speaker, once talking for an hour at a Father Judge graduation at Convention Hall. Democratic leaders endorsed liberal City Controller Alexander Hemphill for mayor, but Young and the labor movement stuck with Tate, helping him overcome Hemphill in the primary and Republican Arlen Specter in the general election.

Young disliked Frank L. Rizzo, a conservative Democrat running for mayor in 1971. He claimed Rizzo told union leaders he’d “beat the s—” out of the Black Panthers.

Rizzo sought the AFL-CIO’s support, but Young was not on board.

“Most of labor in this city is behind you, but I want you to know I’m not supporting you. I think you’re a racist and I don’t agree with any of the stuff you’re doing.”

Rizzo replied by calling Young a “leftist pig.”

Young supported his Northwood neighbor, Bill Green, for mayor, but Rizzo won the primary. Young hated Rizzo so much that he endorsed Republican Thacher Longstreth in the fall, but Rizzo was elected.

Rizzo quickly became close with President Richard Nixon, and Young thought Maine Sen. Edmund Muskie was the man to take on Nixon in 1972. That was until Muskie asked Young, “Wendell, what is the minimum wage now?”

George McGovern won the Democratic nomination that year, and Young headed his Philadelphia campaign out of a Center City office. Young asserts in the book that Rizzo ordered cops to tow his car from the campaign lot 87 times.

Democratic party leader Pete Camiel asked Young to challenge Rizzo in the 1975 primary, but he declined. After Rizzo was re-elected, Young joined others in 1976 in an attempt to recall the mayor. He was arrested a couple of times that year. Though the recall effort collapsed, Young opposed Rizzo’s unsuccessful 1978 attempt to change the Home Rule Charter to seek a third term.

Young was an early supporter of Jimmy Carter’s 1976 presidential campaign and even supported Republican Dick Thornburgh for governor in 1978 because he opposed liquor store privatization (though Thornburgh later changed his mind on the issue).

The only time Young ran for office came in 1980, when he ran in the Democratic primary to challenge Republican Congressman Charlie Dougherty. Young was endorsed by the Mayfair Times and News Gleaner, but finished third in the primary.

Young was deeply disappointed that Bill Green, then the mayor, did not endorse him, despite the fact that Young backed his former neighbor in 1971 against Rizzo. He delivered a letter to Green’s receptionist. Green exited his office, and said, “Wendell, Wendell – wait. I want to talk to you.”

“Forget it,” Young said, as the elevator doors closed.

By 1982, Young was busy trying to save A&P supermarkets from closing. At a big meeting at Abraham Lincoln High School, he asked employees to each take out a $5,000 loan to keep the store open under employee ownership, calling it the “boldest decision in all my years as a labor leader.” In the end, the stores stayed open as Super Fresh, an A&P subsidiary.

The A&P drama kept Young out of the 1982 congressional race. Looking back, he thinks he would have won the race that year, when Democrat Bob Borski ousted Dougherty.

Young remained a political opponent of Rizzo, supporting Wilson Goode in the 1983 Democratic mayoral primary won by Goode. Young, at the urging of party boss Bob Brady, supported Goode over Rizzo (then a Republican) in 1987, even though the Goode administration had bombed the MOVE house, killing 11 people, including five children.

Young acknowledged he was considering backing Rizzo in 1991, but never had to make that choice, as Rizzo died before the general election.

Though Young’s tenure focused on providing good wages, health care and a pension for his middle-class members, he was so supportive of union issues that he joined a picket line with the highly paid Philadelphia Eagles during the 1987 NFL players strike, as replacements played inside Veterans Stadium.

Few things raised Young’s ire than the opening of non-union Carrefour, including a site in the Far Northeast. He led a boycott of Carrefour, which bought a large volume of goods and was able to offer low prices.

“I saw it as a basic struggle to keep the union in existence.”

Carrefour closed in 1993 following a recession, though the Far Northeast property was sold to Walmart, another company Young disliked.

Young retired as president in 2005 following a stroke and diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease.

Among the legacies of the Young-led Local 1776 was it being the first local in the UFCW to win a clause in the contract prohibiting discrimination for sexual persuasion.

“It remains one of my proudest achievements,” Young said. ••