Yen Ho was sitting in a Temple University class when a historic house caught her eye.

She and others in the class were tasked with nominating a property to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places as part of a project. They were looking at various properties and came across Frank Shuman’s house and laboratory.

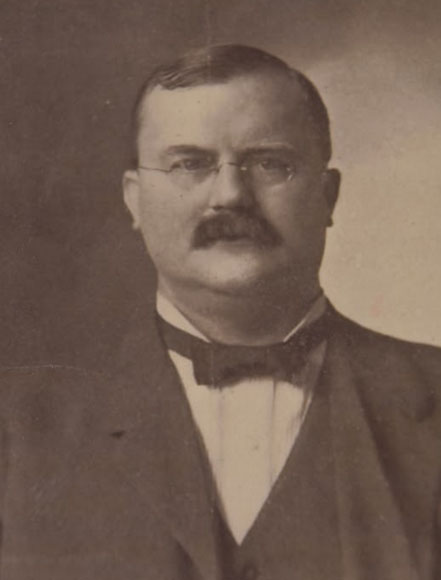

For the final 27 years of his life, Shuman, a prolific inventor, lived in Tacony, where his experiments laid the groundwork for the development of solar energy. His passion even led him to building a solar power station in Egypt.

When Ho heard about Shuman’s life, she found a connection.

“It reminds me about my dad,” she said. “He’s an engineer himself, a scientist, I could say. He does most of his mini-projects in the basement of our house, our cellar.”

A couple of weeks ago, after months of research and fine-tuning, Ho’s application was approved by the Historical Commission. Shuman’s old house, at 4600 Disston St., and adjacent lab, 6913 Ditman St., are now protected.

Neither building can be demolished or significantly altered in the future without the commission’s permission.

“We’ve got a real treasure right in our backyard that so many people don’t know about,” said Lou Iatarola, president of the Historical Society of Tacony, which aided Ho in her application.

Shuman was summoned to Philadelphia in 1891 by his uncle, who ran Tacony Iron and Metal Works. He wanted his nephew’s help in designing a coating for the company’s newest project — crafting the William Penn statue that would top City Hall.

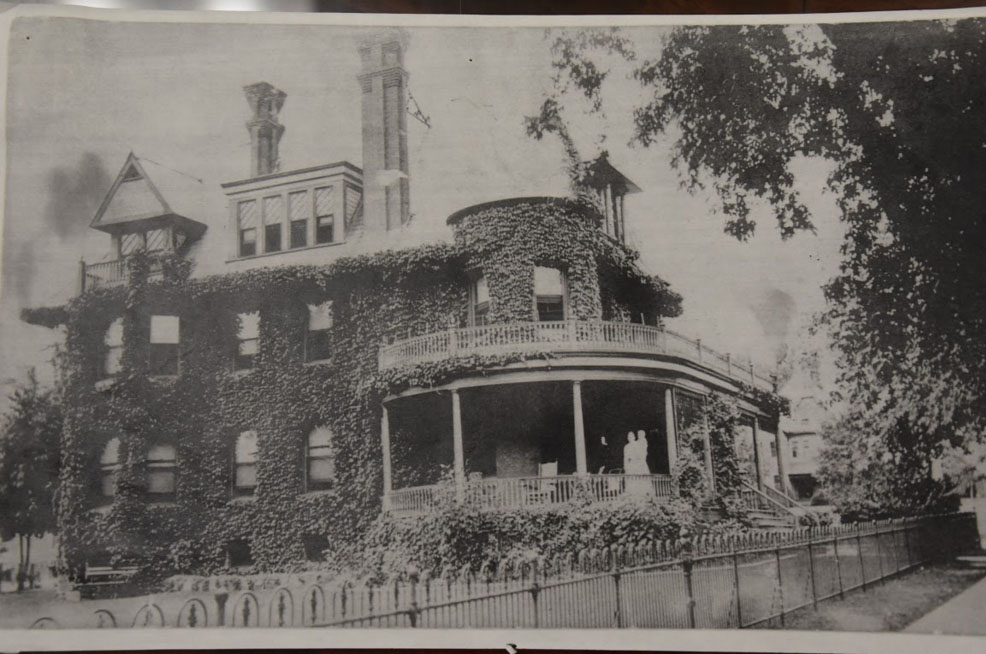

He ended up staying in the neighborhood, building his large home at Disston and Ditman. A historical society photograph from the early 1900s shows the house covered in ivy.

In the 1950s, it was broken up into nine apartments, which is still its current use. The laboratory, constructed between 1895 and 1900, now houses a contracting company.

Ho’s nomination to the commission refers to the two properties as Shuman’s “inventor’s compound.” He was able to fund the operation because of his success patenting a wired glass product that became popular, Iatarola said.

Shuman began investigating the possibility of solar energy in 1906 after Philadelphia passed its first bill to combat pollution, according to Ho’s research.

“The future development of solar power has no limit,” he wrote in Scientific American in 1911. “In the far distant future, natural fuels having been exhausted, it will remain as the only means of existence of the human race.”

The historical society has a treasure trove of photographs and documents relating to Shuman, including a 1907 letter he wrote to another prominent Tacony resident, Thomas South. He was finally ready to give a public demonstration and wanted to drum up press attention.

“This is certainly worthy of all interest, as it is the start of a new era in mechanics; and for our purpose, we want to make as much publicity of it as we can,” Shuman wrote to South.

Iatarola said Shuman ran tests in his yard, laboratory and on fields where Vogt Recreation Center now sits. It was so promising that Lord Herbert Kitchener, of Great Britain, commissioned him to build a sun-powered irrigation plant in 1912 in Egypt.

Unfortunately for Shuman, World War I spelled an end to his great experiment in the desert, though he is still recognized as a solar pioneer.

“Shuman’s solar engine, developed by him between 1906-1918, is today recognized as the first commercially viable solar engine,” Ho wrote in the nomination.

Ho, an Ambler native, has since graduated from Temple and is pursuing a master’s degree in library and information science at Drexel University. ••

Jack Tomczuk can be reached at [email protected].