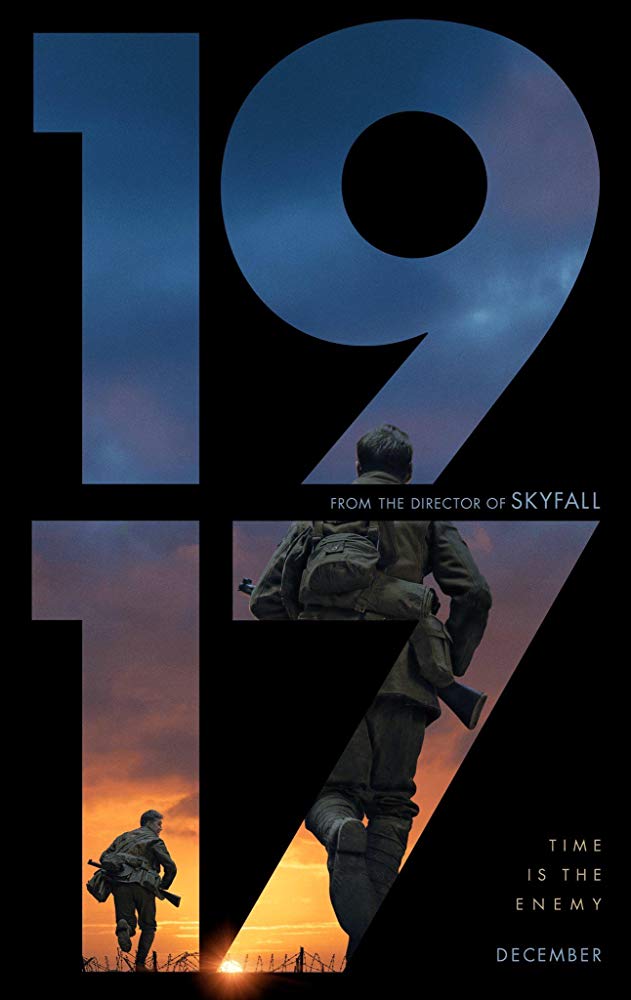

The power of immediacy is what’s most prominently displayed in Sam Mendes’ 1917, a war film crafted to look like one continuous shot through a battlefield in World War I. The camera only fleetingly breaks from our two young British soldier protagonists from the moment they receive a perilous mission to deliver a message to the other side of a war zone.

It’s this real-time, you-are-there intimacy from the unflinching camera that differentiates 1917 from other war films of recent memory, and undoubtedly gave it the edge to snag this year’s best drama picture Golden Globe. 1917 is one for the ages.

Soldiers Schofield and Blake (George MacKay and Dean-Charles Chapman) are awoken from a nap on the edge of a battlefield in northern France and told to deliver a message to a faraway battalion to draw off an impending attack, or else it will fall into the enemy’s trap. 1,600 lives are on the line – including Blake’s brother.

The camera is a silent observer tracking every action and reaction from the two soldiers – Schofield’s recognition this is likely a suicide mission, and Blake’s determination to save his brother anyway, as they gear up and leave in a matter of minutes.

Hyper editing and scene cuts make modern movies go from point A to B in an instant. There’s nothing wrong with that if it benefits the story, but here, Mendes refreshingly makes the time and distance between point A and B the main attraction.

Within the opening minutes Schofield and Blake traverse claustrophobic war trenches before throwing themselves into a no man’s land – a muddy, cratered field strewn with dismembered bodies. Lee Sandales did horrifyingly realistic work on the sprawling sets – scenes have the soldiers ducking behind outcroppings, leaping across muddy ponds and crawling through barbed wire fences, the casualties of war evident with every beat.

The same level of sheer impressiveness continues in the sound design, which imbues every fired bullet or overhead plane with devastating consequence. Cinematographer Roger Deakins is one of the best in the business, and he creates searing, beautiful illusions here. One nocturnal scene illuminates a war-ravaged city via distant explosives and creates a monochromatic scene that’s as stunning as it is terrifying.

The world Mendes and his crew have created certainly isn’t an easy one to inhabit, but it’s a technical masterclass.

The simple narrative is loosely based on stories Mendes heard from his grandfather and was co-written by Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns. It doesn’t strive to assert any new viewpoints about war, preferring to focus on the individual experience and heroics of its main characters. It’s a lot less reliant on dialogue than the likes of Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk, instead relying on the acting to move the emotion.

The cast unanimously does a serviceable job, with MacKay and Chapman guiding the narrative through long, unbroken shots with mostly just the looks on their faces. Mendes pulls from his earlier theater work for the character work, though it’s clear the focus of the picture was its production value.

Watching 1917 is like the best parts of a first-person video game – if you are immersed, it will make you feel like you’re there. The continuous shot is one practiced by the like of Alfonso Cuaron in 2013’s Gravity or Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu in 2014’s Birdman. Both films left their mark and are viewed as two of the best of the 2010s. Mere days into the new decade, we have our first influential film with 1917. It will still be in the conversation at the end of this decade. ••