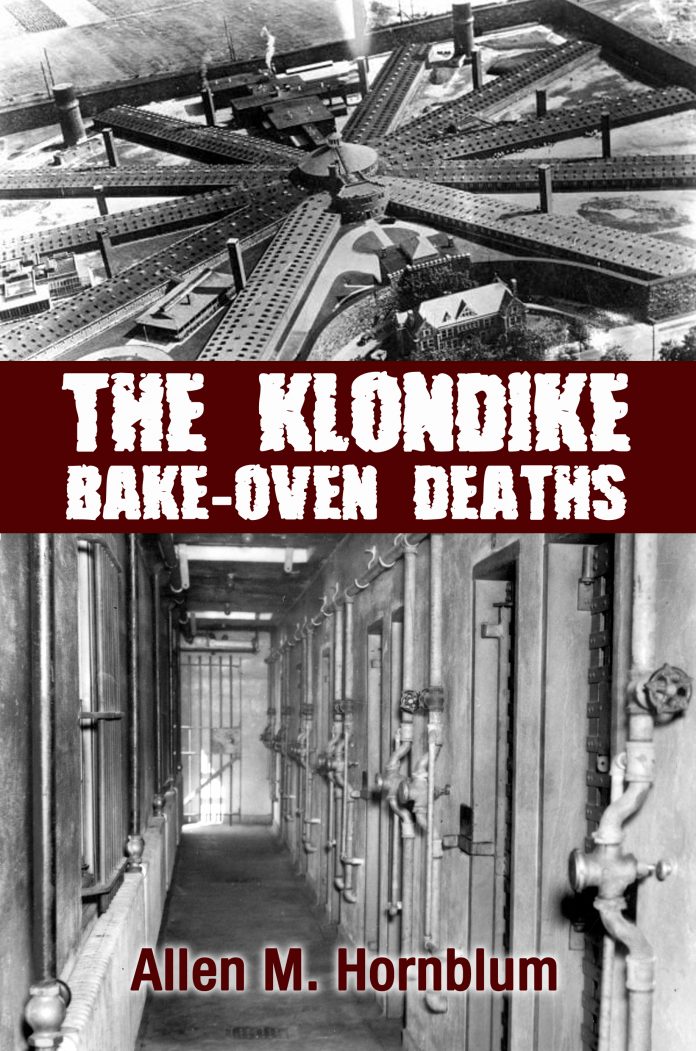

As an author, Allen Hornblum has written books on difficult topics like prison experimentation, Irish organized crime and more little-known topics. When he set out to write The Klondike Bake Oven Deaths, released Feb. 16, he set a new challenge for himself: writing fiction.

The book isn’t entirely from the mechanisms of his imagination – it’s a nonfiction novel, as Hornblum calls it. The premise is based on the true, gruesome cooking of several Holmesburg Prison inmates in an isolated cell block, when guards cranked up the heat in the tightly confined rooms on an already-smoldering summer day in 1938, killing four prisoners. Here, Hornblum takes the horrific event, and its subsequent investigation, and retells it from the perspective of fictional coroner Heshel Glass.

“The story has all the hallmarks of a Hollywood film, don’t you think?” Hornblum said.

This isn’t the first time the author has explored and documented vile acts that took place in the prison, which ceased operation in 1995. Hornblum taught an adult literacy program in the prison in the 1970s, where he learned illegal medical experiments were conducted on inmates for more than two decades. His first book, Acres of Skin released in 1998, made waves internationally with his exposure of the horrific truth.

The Northeast Philadelphian returns to the prison here, but employs a different approach. The switch to fiction allows Hornblum to explore a dramatized version of the real events, which sees a fictional city coroner called to the prison to investigate how eight prisoners (more than the four in real life) ended up dead after a weekend in the “Klondike,” their skin blackened and features unrecognizable even to their own families.

Just like the real events, these inmates are some of those who participated in a recent food strike against the prison’s repetitive and unappetizing menu. Glass (an amalgamation between Charles Hirsch, the city coroner at the time, and Hornblum’s imagination) is driven to expose the truth and find justice for the victims, even though corrupt city officials, guided by a mayor trying to cover up his own negligence, attempt to intervene with his investigation.

In the real incident, guards would back four or five men into a cramped cell, shut the air vents and windows, turn off the water and turn up the heat so inside temperatures could reach 200 degrees. As characters in the book describe, it became too hot to touch the walls or sit on the room’s only mattress. Eventually, it became difficult to breathe.

“It’s just a hell of a story no one knows,” Hornblum said.

Despite the widespread media coverage at the time, Hornblum finds that nowadays people are often surprised such an event took place right in Northeast Philadelphia.

Accustomed to writing pages packed with footnotes and references, Hornblum here trades those in to make room for character study. The 300-page novel marches quickly, advancing the plot while conjuring specific and detailed characters. Even though he dramatized some of the scenes and figures involved, not much exaggeration was needed to make the story a page-turner.

“Almost all of my books are interesting subjects that somehow fall through the cracks,” Hornblum said.

A man of detail, wit and an insatiable appetite for knowledge, Hornblum has never been one to shy away from a self-imposed challenge. Satisfied with his round with fiction, he’s returning to nonfiction for his next book. You may not have heard about whatever topic he’s decided to embark upon, yet. But it’s a guarantee it’ll fascinate you. ••