Tucked away at the corner of Tacony and Bridge streets just below I-95 lies the Frankford Arsenal, a campus of buildings formerly used as a design and development space for artillery initially constructed in the early 1800s by the federal government. The campus expanded over the years before it was closed by the Carter administration in 1977. Two of those buildings, Building 38 and Building 39, were recently purchased by Weizer Management, a company that is turning both buildings into shared kitchen spaces for local food-based businesses, such as food trucks, pickling companies, canning companies, meal prep companies, bakers and catering companies. Building 39 will also play host to an event space and already has tenants operating out of the shared kitchen space. Building 38 is currently still just a shell of a building, but will soon play host to a shared kitchen space called the Culinary Collective of Philadelphia.

“[Building 39] was built in 1917 and functioned as a paint shop where artillery shells and vehicles were painted off,” said Brandon Weizer, chief operating officer at Weizer Management. “It sat empty for years until we acquired it in 2019.”

According to Weizer, only a handful of companies had occupied the building since the ‘70s, including a high-end auto interior design company.

“For the most part, it stayed a shell and trapped in time since whenever the military had vacated that property.”

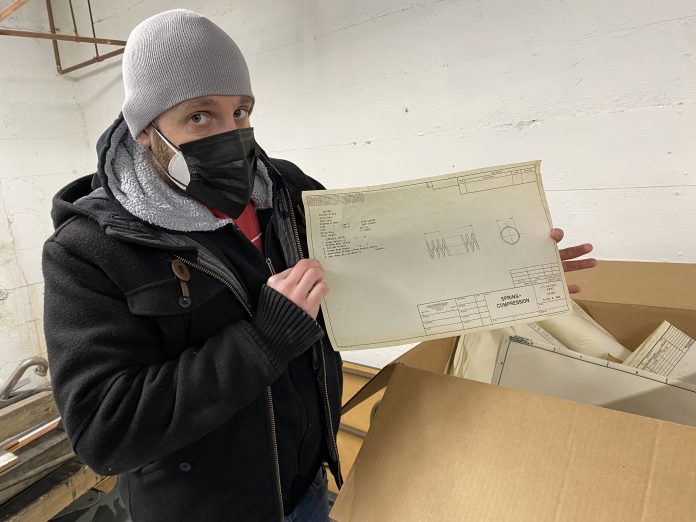

In the basement of both facilities, Weizer found artifacts from the buildings’ history, including several 76 mm shell casings believed to be constructed for the M18 Hellcat, a tank used by the United States military during the Korean War and World War II. Also found were documents that appear to be blueprints or sketched-out designs of certain materials used for weaponry.

Weizer Management also owns the Bridesburg Commissary just around the corner. It bought Buildings 38 and 39 in part for the easy access to I-95, the large parking lot and the ability to design an event space that supports mobile food trucks. But also to “assist in reviving the Frankford Arsenal campus,” said Weizer. “I’ve driven past there countless times and I had no idea what it was.”

Both Buildings 38 and 39 were connected to other buildings in the complex via an underground tunnel, which had to be sealed to prevent “nasty” air from coming through, according to Weizer.

The Frankford Arsenal “pioneered mechanized production of munitions and developed numerous important innovations in ordnance and precision Instruments,” reads a historical document about the arsenal written by historian Patrick O’Bannon in 1988. “Technological Innovations introduced at Frankford Arsenal made important contributions to the mechanization of American industry and the Implementation of interchangeability and mass production techniques.”

According to O’Bannon’s document, Philadelphia was an “obvious candidate” for the arsenal at the time of construction because of its status as a seaport.

“[T]he city could be easily defended in time of war,” wrote O’Bannon. “Philadelphia’s role as the nation’s leading seaport, with well-established mercantile connections to other countries, and Its leading position within the nation’s growing powder industry, also made it an attractive location for an ordnance installation.”

The Frankford Arsenal was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. The facility’s nomination to the NRHP argues that while the arsenal’s prime period of significance was during the 19th century, it served important roles during the 20th century as well. For instance, in the late 19th century, the arsenal developed into the explosives testing center of the United States.

“Optics and fire control research became the Arsenal’s major scientific endeavor during the twentieth century,” the nomination reads. Prior to World War I, the Frankford Arsenal “developed into the explosives testing center of the United States,” the nomination also reads. “[B]ut by 1900 this work had largely transferred to Sandy Hook Proving Ground in New Jersey, because the newer and more powerful explosives and ammunition required more space for testing than could be provided at Frankford.”

Weizer called Weizer Management “a commercial real estate development company focused more on kitchen infrastructure,” that was started by his father and grandfather. ••