“Oh, that stuff,” the woman behind the counter said.

She and a co-worker had answered with blank looks when they had been asked if their Frankford Avenue convenience store carried “Kryptonite,” “K2” or “Chronic.” Asked about “Kush,” one nodded.

“I don’t know if we still have any,” she said, and then directed another co-worker to “look in the safe.”

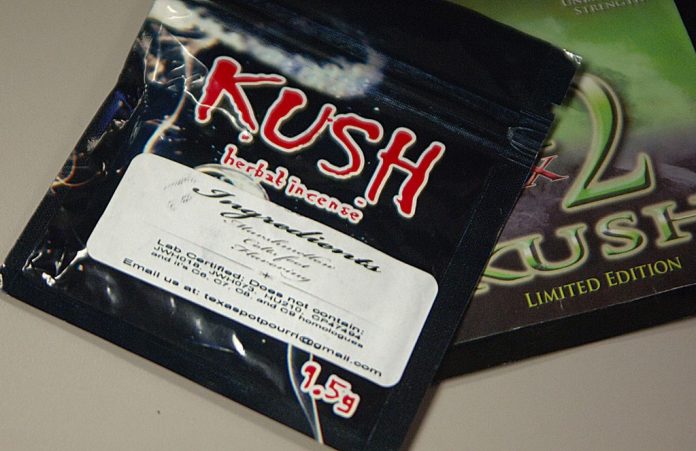

The Kush sold at the store came in a 3-inch-by-4-inch foil envelope clearly marked as “herbal incense.” The small package’s 1.5 grams (about a teaspoon) sold for more than $14, including state sales tax. It also was clearly labeled that it was not for sale to minors and that it was “not intended for human consumption!”

Well, that might be true if you confine the meaning of the word “consumption” to a synonym for “eat.”

People don’t eat it, one convenience store worker told a reporter. They smoke it to get a marijuana-like high, one they believe to be a legal high, and one they believe won’t be detectable if their urine is tested for marijuana, the store worker said.

People going to drug rehabilitation programs on Frankford Avenue seem to share the belief that they’ll test “clean” after using Kush or products like it to get high, the store worker said. It’s a big selling point, he said. Whether the people who smoke it actually get high might be a matter of personal interpretation.

And whether they get legally high is subject to interpretations that might not be easy to understand.

Kush was labeled as “lab certified” that it did not contain an alphanumeric soup of ingredients. At another convenience store not far from the first, a similar envelope sold as “unbelievable strength” K2 Kush was labeled as being “DEA compliant” — whatever that means, said Nils Hagen-Frederiksen, a spokesman for Pennsylvania Attorney General Linda Kelly.

It’s probably B.S., Dawn Dearden, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, said last week.

Synthetic marijuana is not legal in Pennsylvania and hasn’t been since a law that also made so-called “bath salts” illegal went into effect in March 2011, Hagen-Frederiksen said in an interview on Friday.

Dearden said what is known generally as synthetic marijuana is material that is sprayed with substances that can mimic the ingredients in real marijuana that produce its high. The chemicals sprayed are called synthetic cannabinoids, she said. So what is it sprayed on? One of the products a reporter purchased last week in Frankford said it contained hops and lemon balm as well some other common, easily grown plants.

There are hundreds of synthetic cannabinoids, Dearden said. More than a year ago, the DEA “emergency scheduled,” or temporarily banned, five of them.

Since then, “chemists” have begun using other similar, but not banned, cannabinoids, she said.

As far as testing “clean,” users might be right, she said, adding she doesn’t think there are drug tests that will detect synthetic marijuana. But, she said, she believed tests are being developed to spot it.

There’s nothing on the labels of Kush or K2 Kush — or other products similarly packaged — that describe them as synthetic marijuana or marijuana-like.

Look on the Internet, though, and it’s easy to find sites and blogs in which the effects of these products are described, explained, praised or derided. Some bloggers said they thought these products provide nice highs, but other bloggers said they felt their hearts racing or experienced other scary reactions.

Dearden said users don’t really know what they’re getting from product to product or from vendor to vendor. A “chemist” might spray on a substance in a quantity that makes it several times more powerful than real marijuana.

“It’s a crap shoot,” she said, adding there have been reports of medical problems like racing heart rates and the shakes.

The safety of these products is not only in question, their legality remains uncertain, too.

That came up at a recent Frankford community meeting. The owner of a neighborhood convenience store wanted to know if the stuff really is illegal. He produced a distributor’s mailing he had received that encouraged him to stock up on “Kryptonite” before a ban goes into effect.

Two police officers at the meeting said they didn’t know about that. The storeowner said he had heard another local business owner had been arrested for selling it, but Tasha Jamerson, a spokeswoman for District Attorney Seth Willams, said she didn’t know of any such prosecutions.

Dearden said that, when the DEA “emergency scheduled” the five chemicals most often used to manufacture synthetic marijuana, the agency was inundated with phone calls from storeowners who wanted more information about the ban.

That was in 2010, she said, so anybody who is still selling the stuff has since restocked.

Dearden said the U.S. Senate is considering a measure that would more generally outlaw the chemicals used to create synthetic marijuana.

But users and sellers have some things to keep in mind.

Just because the label on a product says it doesn’t contain the banned chemicals, Dearden said, doesn’t mean that it really is free of those substances. That should be an important consideration for anyone who sells it, Dearden said.

Why? She explained that it’s the person who sells a banned substance who gets into trouble — just like any drug dealer would.••