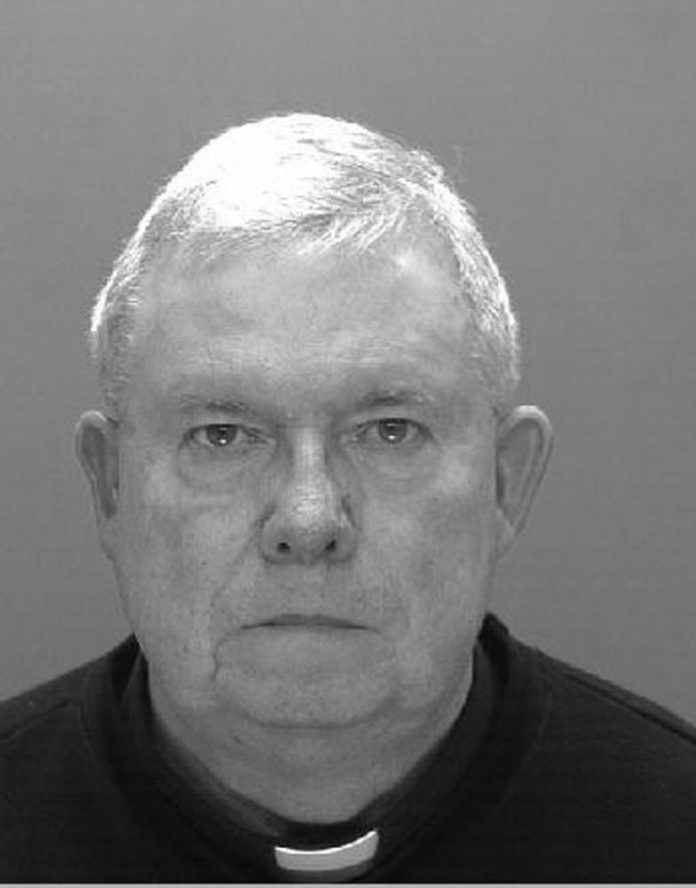

Monsignor William Lynn, the highest-ranking Catholic cleric charged with shielding child molesters, did just the opposite, one of his lawyers claimed Monday.

Lynn, said attorney Thomas Bergstrom, did everything in his power to get priests suspected of abusing minors away from children. But, Bergstrom said, decisions on those priests were not his alone. Ultimately, those decisions rested with Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua, head of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia when Lynn worked as secretary for clergy and investigated child abuse cases.

The cardinal died in January, but his videotaped testimony might be heard in the trial of Lynn and the Rev. James Brennan, who is charged with molesting a teenager during the 1990s and with conspiracy. Lynn is charged with conspiracy and endangering children for shielding Brennan and former priest Edward Avery.

Avery, who was defrocked, last week pleaded guilty to molesting a St. Jerome’s parish altar boy in the 1990s and to conspiracy charges. He was immediately sentenced to two and a half to five years imprisonment. He had been scheduled to go on trial with Lynn and Brennan this week.

In opening statements Monday, prosecution and defense attorneys offered jurors two distinct perspectives of the evidence they’ll see in what could be a very long trial.

The prosecution painted the case with a broad brush, claiming the church spent years trying to avoid scandal rather than protect children. Defense attorneys contended the charges against their clients were very narrow and that the evidence and testimony presented in what is expected to be a four-month trial will show the defendants are not guilty.

Citing the cases of many uncharged priests, several of whom had worked at Northeast parishes, Assistant District Attorney Jacqueline Coelho said Philadelphia’s Roman Catholic archdiocese spent years protecting itself from the scandal of sex abuse by its clergy rather than protecting the children they allegedly molested.

The problem was kept a secret, she said. It was that secrecy that Lynn participated in when he was Bevilacqua’s secretary for clergy from 1992 to 2004. The charges against him are that he endangered children who were molested by Brennan and Avery by keeping allegations against them secret and by allowing them to continue to serve in ministries in which they had access to minors.

Proving the case will be long and complex, Coelho said, but the crime itself is simple.

“This is a pretty straightforward crime,” the prosecutor said. “It’s just common sense; you don’t put children at risk.”

Early in his tenure as secretary for clergy, she said, Lynn had enough knowledge to understand the nature of the archdiocese’s problem with priests who molested children.

But, she said, “Lynn’s concerted effort was to protect the church from scandal.”

Bergstrom countered that he would not debate that there is a Catholic Church sex scandal.

“It is a documented truth that sexual abuse of children happened in the Catholic Church,” the attorney said.

But he said he would defend Lynn against a narrow set of charges that he had facilitated that abuse and he said there were no grounds for the conspiracy charge against Lynn.

Lynn, Brennan, Avery and two others were arrested in February 2011 after a grand jury issued a report on its investigation of sexual molestation allegations against Philadelphia’s Catholic clergy.

The five, which included the Rev. Charles Engelhardt and former St. Jerome’s parish school teacher Bernard Shero, initially were not charged with conspiracy. Prosecutors later added conspiracy charges, although that charge against Shero was subsequently removed by a judge. Engelhardt and Shero will be tried later.

Bergstrom said Lynn had never spoken to or met the men who said they had been molested by Avery and Brennan when they were minors.

“Yet, he is charged with endangering their welfare,” Bergstrom said.

Attorney William Brennan, who is not related to his client James Brennan, said there is no grand conspiracy involved in his case. He said 99 percent of the case against Lynn has nothing to do with Father Brennan. There is just one witness against Brennan, the lawyer said, and he told the jurors it was up to them to see if that witness is reliable.

The lawyer claimed that witness was a man who had a troubled youth and that he has been convicted of several crimes, including falsely reporting an offense that had not occurred. Once jurors see that witness is not believable, the attorney said, the case is over.

In her opening statement, Coelho had told jurors this is “a paper case,” involving boxes of documents.

That statement was underlined by the first prosecution witness.

In the first three hours of his testimony Monday and Tuesday, Joseph Walsh, a district attorney’s office detective, read and answered questions about almost 50 documents.

Twenty jurors were able to read along with the detective on two large-screen TV screens placed near their seats and on a large projection on the opposite wall.

Documents Walsh read under questioning from Assistant District Attorney Patrick Blessington dated back to early 1992 and 1993 and concentrated on Monsignor Lynn’s knowledge of sexual misconduct allegations against Avery.

On Monday afternoon and Tuesday morning, Walsh went over documents that detailed Lynn’s reactions to a complaint from a then 29-year-old married medical student that Avery had fondled his genitals and had given him beer when he was a teen.

Most of the prosecution exhibits were internal archdiocesan memos about the complaints and directions for Avery’s psychological evaluation, treatment and assignments.

However, by Tuesday morning, Walsh was reading letters from Avery’s parishioners who praised him and were concerned about his whereabouts.

In August 1993, after months of treatment, Avery resigned as pastor of his Mount Airy parish. Lynn, according to documents shown in court, told parishioners that Avery resigned for health reasons.

There originally were 12 jurors and 10 alternate jurors chosen, but two were removed Monday morning after Common Pleas Judge M. Teresa Sarmina and attorneys questioned them about their knowledge of Avery’s guilty plea.

The trial is continuing in Courtroom 304 of the Criminal Justice Center, 13th and Filbert streets. ••