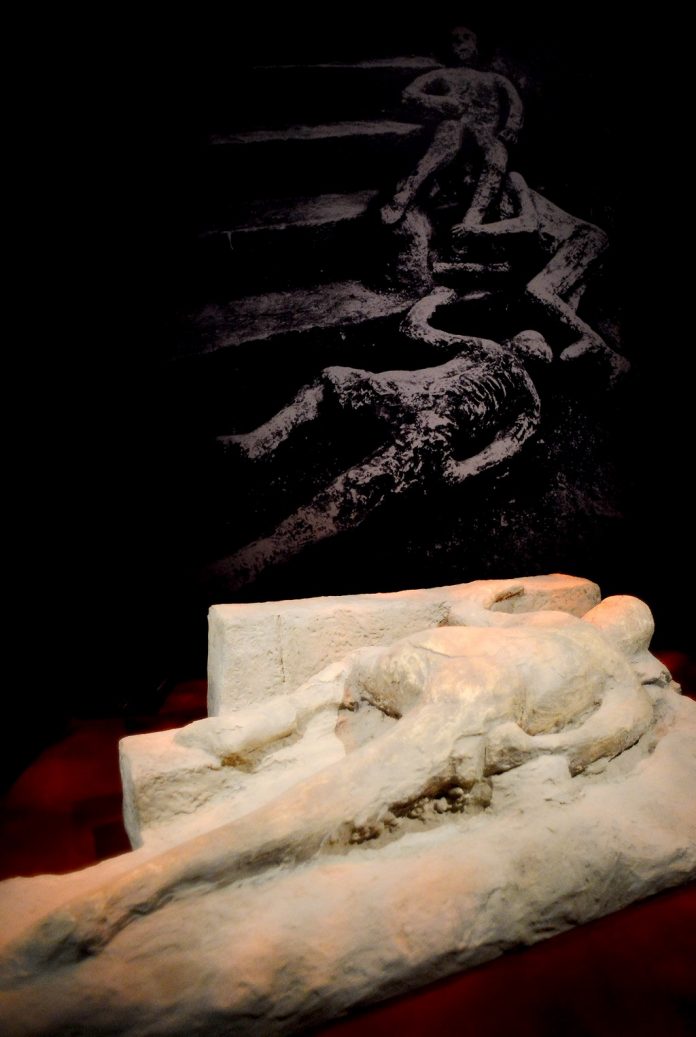

Another cast of a person that died falling on the stairs. Behind him, is a photo of the excavation site in Pompeii as he was found with several others.

The ancient Roman city of Pompeii remained frozen in time for more than 1,500 years absent the touch of human hands, buried in a volcanic tomb created by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D.

But now that its treasures have been unearthed and revealed to the modern world, Pompeii’s walls have begun to crumble.

Weeks of heavy rains and wind in the Italian coastal province of Naples have been wreaking havoc on the popular tourist attraction and UNESCO World Heritage Site. Archeologists and advocates have blamed mismanagement and political neglect for delays in a planned restoration project, according to published news reports.

Meanwhile, Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute continues to draw throngs of folks seeking to immerse themselves in the culture and the catastrophe of the fabled city. The exhibition opened on Nov. 9 and will remain on display until April 27.

One Day presents about 150 artifacts on loan from the definitive Pompeii collection of the Naples National Archaeological Museum. The objects range from affluent sculptures, paintings, coins and jewelry to common tools, cookware and utensils salvaged from the ancient city.

“Unlike other natural disasters that destroy all that’s in their path, nature destroyed Pompeii, but it also preserved it,” said Dennis Wint, the Franklin Institute’s president and CEO, during a Nov. 7 preview tour. “The exhibit tells the story of the life and death of this ancient Roman city.

“The exhibit gives an extraordinary look at Pompeii’s archeological treasures that are rarely seen outside of Italy and are here at the Franklin Institute. … The objects include lifesize frescoes, marble and bronze statues, jewelry, coin and full body casts of the volcano’s tragic victims.”

The legendary eruption of Mount Vesuvius began on Aug. 24, 79 A.D. At the time, Pompeii was a prosperous town-city of about 25,000 inhabitants at the base of the mountain. The settlement featured an amphitheatre, gymnasium, baths, water system and elaborate residences, many of which featured central atria where the occupants reveled in their Mediterranean lifestyle.

The city derived much of its wealth from its rich agriculture and bustling maritime port. Slavery also played a crucial role in the local economy. Yet, some slaves were paid for their labor and could save their earnings to buy their own freedom.

Prior to the devastating eruption, Pompeii had long been the locale of periodic earth tremors. In 62 A.D., a major earthquake damaged most of the city. Many inhabitants fled for good, but those who remained rebuilt.

They knew nothing of their fate. In fact, a term for “volcano” didn’t exist in the Latin language they used.

Seventeen years later, the long dormant Vesuvius exploded, spewing ash into the sky and molten rock into the valley below. Ash and embers rained on the city, setting much of it ablaze. The next morning, lava flowed through the city streets, burying them beneath almost eight feet of volcanic debris.

Most inhabitants escaped in time, but the disaster claimed about 2,000 lives.

In the centuries to follow, the absence of air and moisture preserved much of the city virtually intact. By the early 18th century, history knew of the disaster from recorded witness accounts, but Pompeii was thought to have been destroyed, literally erased from the landscape.

In about 1709, a farmer digging a well struck the ancient theater of Herculaneum, a town near Pompeii that also perished in the infamous eruption. The farmer continued digging and found the ancient marble sculptures. Soon, an Austrian general bought the land and spent the next two years digging tunnels to plunder the subterranean treasures.

For the ensuing 150 years, a succession of conquering rulers mounted numerous excavations of the territory. Some, including Napoleon’s sister Queen Caroline Bonaparte Murat, systematically surveyed and catalogued their findings.

Since then, various efforts have focused on uncovering and restoring the principal streets and buildings of the ancient city, which has survived scavengers, Allied bombings during World War II, another volcanic eruption in 1944 and an earthquake in 1980, among other threats.

Today, the ancient city occupies about one-quarter square mile. One-third of the city remains underground while the archeological focus has moved from new excavations to conserving the structures already unearthed and researching the early settlement of Pompeii.

Daytime tickets for One Day in Pompeii cost $27.50 for adults and $21.50 for children and include general admission to the Franklin Institute. Evening tickets cost $18 (adults) and $11 (children). The rest of the museum closes at 5 p.m. Call 215–448–1200 or visit www.fi.edu for information. ••

An example of the city’s cookware is also on display.

A glimpse into history: In 79 A.D., after the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in Pompeii, many people became literally frozen in time underneath dozens of feet of ash and volcanic mud. This man died covering his face from the intense heat.

In front of the many city homes were statues of Roman Gods and soldiers. ‘One Day in Pompeii’ is currently on exhibit at the Franklin Institute.

A fallen city: A fountain currently on display at the Franklin Institute is an example of what people would have in their house gardens, which was in the middle of each Pompeii home. MARIA POUCHNIKOVA / TIMES PHOTOS