Valerie Felici rarely shares her poems on social media, but in the days following the death of her oldest son, she had to.

“Addiction does not define my son,” part of a poem she published in a Facebook post reads. “His name, his loving heart, his beautiful smile, all his good deeds, his willingness to help others outweighs by a ton.”

Writing helps Felici process her emotions, and her family’s worst nightmare had come true. On Feb. 24, Ned M. Felici Jr. passed away in his home due to a drug overdose, leaving behind his parents, siblings and his son. He was 25 years old.

But amidst the grief, Felici chose not to remain silent. A police officer and volunteer in the city, she has seen that her son was not the only one in Northeast Philadelphia to struggle with addiction. She was asked to speak at a meeting held recently about mental health and addiction at Friends Hospital hosted by state Rep. Joe Hohenstein. The grief was still fresh, but after deliberating, she decided to speak from the heart.

“I said listen, to all you doctors and people sitting here feeding us stats, your stats are great, but they’re not helping anybody,” she said. “We’re putting all this money into you doing stats instead of where it really needs to be, which is treatment and health and mental health. We need solutions.”

She said 13 state representatives attended the meeting, but only five hadn’t left by the time she got to speak.

Less than a month after Ned passed away, Felici invited Far Northeast resident Scott Kilpatrick to her home. The two were just meeting for the first time, but they were both members of a club no parent ever wants to be in. Kilpatrick’s son, Nick, had passed away Dec. 22 of last year due to an overdose. He was 19.

Kilpatrick is a new member of Never Surrender Hope, an organization co-founded by Felici. Members will drive around the city, particularly in Kensington, and deliver supplies, food and information to people struggling with addiction and homelessness. Most of its members are from Northeast Philadelphia.

“We’re from Northeast Philadelphia because the problem is so high here in Northeast Philadelphia,” Felici said.

The sons

Felici and Kilpatrick had a lot in common in their experiences, including they had both been good parents to good kids.

Ned had the ability to charm anyone, Felici said. He worked in construction, but eventually quit his job to get treatment. He had a son, Ned III, who turned 7 just four days after his father passed away.

“Ned would run next to Neddy riding his bike and they always laughed as Neddy would go faster and faster and Ned would try to keep up,” Felici said.

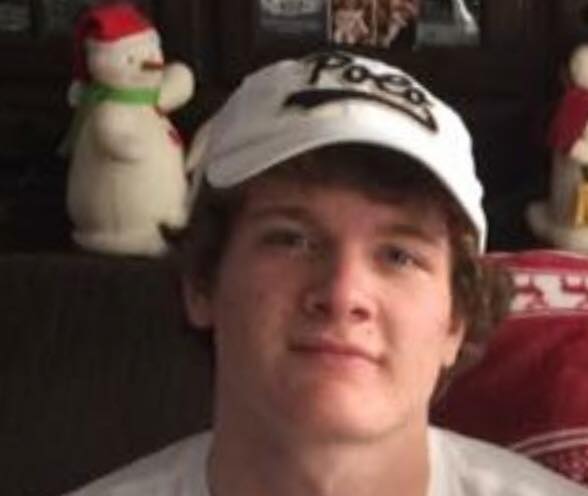

Nick Kilpatrick was loyal, passionate, a risk-taker and an original, his father said. When he was in school at Father Judge High School, he was part of a bully patrol and would get involved if he saw bullying, even though he was described as skinny. He played hockey as the goalie, though Kilpatrick said he wasn’t a normal goalie.

“He played like Ron Hextall and in this day and age you just don’t,” he said with a laugh. “One time his coach said he could be a leader of men, it just depends on which way he wants to take them.”

Nick and Ned both grew up with parents who urged them not to do drugs, but, as Felici said, you can’t monitor their lives 24/7.

“How Ned’s addiction started was him behind Ryan at a keg party like they did on the weekends, the rite of passage for all teenagers,” Felici said. “Taking that one pill, him and his friends never realized the damage. And that was it, that was it from there.”

“Maybe someone makes a choice to take a pill, but no one expects to become addicted to the drug,” Kilpatrick said.

Although his grief can sometimes get the better of him, he decided he’s going on a “mission” to keep his son’s legacy alive, which includes joining Never Surrender Hope and obtaining a family recovery specialist certificate so he could help out families in need.

“You raise your kids to be productive adults. A part of me feels I failed, and I’ll take the blame for it. But for my son to be laying on a set of bleachers for 16 hours, got walked away from, until I had a gut feeling something was wrong,” he said.

“Trust me, I could crawl into a corner, but inside of me I said I’m not going to let his legacy die. My kid could have had a productive life as an adult. He had a lot to offer to this world. But I’m on a mission right now. My grief kind of gets to me and I get a little tired, but I won’t stay down. This is something no parent should have to experience.”

Struggling to find treatment

“When I found out my son had a drug problem I realized the only way I could truly help my son was to understand addiction,” Felici said. In her efforts to try to find help within the city, she said she discovered a lack of resources, empathy and support for those seeking help with addiction in Philadelphia.

Ned went to 40 treatment centers in his journey for recovery. None of them offered a dual diagnosis, meaning identifying a mental health issue that could impact the patient’s struggle with addiction. Ned suffered from depression and anxiety, Felici said, which could at times turn him into “his own worst enemy.”

“The mental health aspect when it comes to addiction is never fully addressed,” she said. “And they can not address that in 28 days, your average treatment stay. There’s no way in 28 days, you’re going to tell me they can address mental health issues along with addiction issues and think you’re going to have somebody mentally stable to leave and come back out to the streets to leave and get their own outpatient treatment.

“It’s not going to happen. It will never happen, and as long as that continues to happen, we’re going to have people continuing to die.”

Kilpatrick said the only way to fully understand what individuals with addiction go through is to have experienced being an addict themselves.

“If my son talked to someone who had went through the same thing he would have been much more receptive,” he said.

Both agreed that no other disease has stigma attached to it like addiction. Felici was exposed to the prejudice every time she logged onto social media, seeing it on local Facebook pages, her own son’s page, Kilpatrick’s son’s page and the Northeast Times’ page.

“The people of the Northeast, they shame,” she said. “If you’re so sick from the crime that the so-called ‘junkies’ – I hate that word – are doing, how are we going to stop it? Get them the proper treatment and support they need.

“People in the Northeast want to act like we’re this great people. We’re not from North Philly, we don’t live in the badlands. The Northeast isn’t better than all these places – we’re exactly the same, but you act as if you’re better than them.”

Growing up in Fishtown, Kilpatrick said he was empathetic toward those struggling with addiction, but always assumed it would never impact his kid.

“When I found out my son was using heavy drugs I blamed myself, what did I do wrong,” he said.

Felici, who works for the police, offers other officers instruction on how to handle an overdose situation. When her students learn that her son struggled with addiction, they’re surprised.

“People always thought we had the perfect family. A mom and dad who were cops, everybody knew we loved our kids because we were always involved in everything they did,” Felici said. “Guess what, to me it was the perfect family, and Ned’s addiction didn’t change that.”

Addiction can have any face in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania or the country, though that doesn’t mean the disease defines the person, Felici said.

“People who deal with substance-abuse disorder define them by that,” she said. “Nothing else they’ve done in life, just that they’re an addict. My son wasn’t defined by addiction. It was just a little piece of them, but he was so much more than an addiction.” ••